Jain Sculptures and Art Collections in Museums

Chariot composed of calculations at the Asian Art Museum, San Francisco

By Dhruti Ghiya Rathi

Dhruti is a New Jersey-based MBA, SAP and FJAS professional. A Pathshala and guest lecturer for Jainism at VCU University and High schools, she has spoken at Comparative Religion Conference, Religious Baccalaureates and Rotary Club in Richmond, VA. Involved with Jainism-Says-Blogspot, she researches Jain Iconography, Epigraphy, Historical and Numismatic references in Jain literature overlooked by historians, and on the applications of Jain principles. Dhruti’s research was presented at the Dating of Mahavir Nirvana Symposium by ISJS. dhrutirathi@gmail.com

As a part of our series on Jain Art and Sculpture, we bring to you exciting information about a painting from the Asian Art Museum, San Francisco that has puzzled the visitors as well as the curators of the museum. The content and the details of the painting have been a mystery so far. The museum identifies the painting as:

Chariot composed of calculations, from an unidentified Jain manuscript:

Fig 1 DATE: Approx.1400-1450, PLACE OF ORIGI N: I ndia; Gujarat state MEDIUM : Ink and colors on paper DIMENSIONS H: 4 1/2 in × W. 10 in CLASSIFICATIONS : Painting CREDIT LINE: Gift of Betty and Bruce Alberts DEPARTMENT : South Asian Art NUMBER : 2021.111 ON VIEW : GALLERY LOCATION 3

The Asian Art Museum, San Francisco, has a painting depicting a chariot with numbers that are presently presumed to be indicating some horoscope calculations. Per the Museum: “Some followers of the Jain religion were, and sometimes still are, interested in horoscopes, the calculation of auspicious dates, and the deriving of mathematical formulas thought to underlie the structures of the world This more than five-hundred-year-old painting shows characteristics of early western Indian manuscript art. The artist gives the horse and charioteer bold, easily readable silhouettes. Typical of the period are the pointy facial features of the charioteer and his “protruding eye:”, the eye on the farther side of the face sticks out beyond the profile We don’t know what the numbers and calculations shown here within the outline of a chariot signify. The museum requests any further information on the calculation numbers in the painting ”

An Illustrated Ardhamagadhi Dictionary by A C Woolner and Ratnachandrji 1 identifies the above painting as 18000 Shilang Rath (Chariot with 18000 Jewels of Right Conduct (Charitra) for a Jain Monk), based on the Panchashak written by Haribhadra Suri Haribhadra’s timeline as concurred by Jacobi, A. N Upadhye, Hiralal Jain relates to 750 CE. A. Barth suggests

1 An Illustrated Ardhamagadhi Dictionary, Ratnachandraji, 2nd edition, Motilal Banrasidass 2016, Vol 1 Pg.131

his period as the 9th century CE Haribhadra Suri was a Brahmin scholar highly well versed in many languages with knowledge of Vedas and other scriptures. He was a great debater and had a lot of pride in his debating skills. He vowed that if he came across a shloka that he could not understand, he would become that person’s disciple. He came across a Sadhavi reciting a sutra from Acharya Jinbhadra’s (6th -7th century CE) Sanghrani that he could not understand, and hence he became a disciple of Acharya Jindatt (or Jinbhadra or Jinbhatt). Prabhavak Charitra and Prabhandh Kosh indicate Jinbhadra as the Guru of Haribhadra. 2 He is known to compile about 1400-1440 granths, of which presently only 100 of them have been discovered. The 18000 Shilang Rath caters to the Right Conduct (Samyak Charitra), an essential requirement for the monks on the path towards Moksha or Salvation. Haribhadra gained this knowledge on the Samyak Charitra from Acharya Jinbhadra’s work Dhyan Shatak (Book on Meditation consisting of 105-106 couplets).

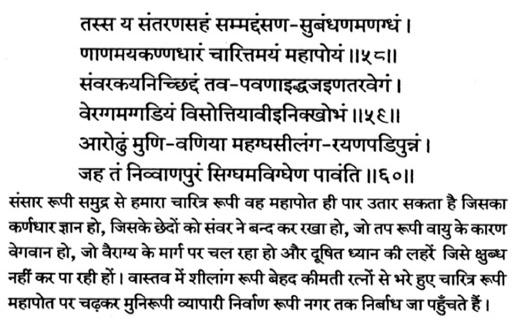

Couplet 60 of Dhyan Shatak by Acharya Jinbhadra presented below in Fig 2 mentions how a Jain Monk can ride on a chariot consisting of Jewels of Right conduct and hastily travel the path towards Moksha or Salvation The initial stanza in Prakrit is followed by translation into Hindi for better understanding. 3 Fig 3 portrays Jinbhadra emphasizing the praise of Jinendra Tirthankara and those who follow the principles of Jain Agams, Right Conduct (Shil) and Control. He considers them as true meditators and followers of Jainism Jinbhadra also authored Sangrahani (Bruhat/Trailokya) which details various calculations explaining various Jain concepts.

Fig 2 Fig 3

Acharya Haribhadra (750 CE) wrote a commentary on the Avashyak Sutra, the first Jain Agam, in which he refers to this important compilation on Dhyan by Jinbhadra, and changed the original name from Dhyanadhyayan to Dhyan Shatak, as it contains over 100 couplets Haribhadra, thus obviously had the details of the 18000 Shilang Rath from Jinbhadra, who compiled it before him. The Chariot calculations can be understood from the text of Panchashak (Fig 4) by Acharya Haribhadra where the numbers are mentioned in words and highlighted 4 Elaborating on Jinbhadra’s work, Haribhadra explains the categories and the calculation numbers. The 18000 Shilang Rath as shown in An Illustrated Ardhamagadhi Dictionary 5 is also presented in Fig 5 for comparison and it also gives reference for the image as Panchashak by Haribhadra.

Fig 4 Fig 5

Incidentally, the order of the ten virtues of Jain Dharma is different in current times, as compared to what is described in Panchashak. The artwork in Fig. 5 also shows the order in a slightly different manner than listed in the Panchashak.

2 PhD Thesis on Jinbhadragani Krut Dhyanshatak evam uski Haribhadraiya Tika Ek Tulnatmak Adhyayan by Priya shraddanjanashree ji, jainelibrary.org, sr no. 003973, Pg 37

3 Dhyan Shatak, Jinbhadra Gani, Jaykumar Jalaj, Manish Modi, jainelibrary.org, sr.no 022098, Pg 21,22

4 Panchasak Mulam, Haribhadra Suri, jainelibrary.org, sr.no 020535

5 An Illustrated Ardhamagadhi Dictionary, Ratnachandraji, 2nd edition, Motilal Banrasidass 2016, Vol 1 Pg.131

However, the painting, Chariot with calculations, matches completely with the order and names of the ten virtues Jain Dharma listed in the Panchashak and shown in Fig 6. Hence, this further establishes that the Chariot with Calculations is based on the Panchashak manuscipt by Haribhadra of 8th century CE.

Fig 6

Next, let’s now understand the content of the painting Chariot composed of calculations from an unidentified Jain manuscript (Fig 7), identified here as the 18000 Shilang Rath, from Acharya Haribhadra’s Jain manuscript Panchashak

Fig 7

Starting from the bottom, the first line describes the ten virtues of the Jain Dharma, which are to be followed by all Jain Monks and consist of Kshama, Mardav, Arjav, Muti (Aparigraha), Tapa, Sayam, Satya, Soch, Akinchya and Brahmacharya. Each virtue is described as having the value of one. All these ten virtues should be applied by the monk in his behavior towards living and nonliving things, which are described in the second line from the bottom. They are Prithivikaya, Apkaya, Tapakaya, Vayukaya and Vanaspatikaya (all Ekendriya beings with one sense), followed by the beings with two senses Beindrya, beings with three senses, Teindriya, beings with four senses, Chaurendriya, and beings with five senses, Panchendriya. The last box in the second line from the bottom mentions Ajivikaya, which includes primarily matter, and medium of motion, rest, and space. Contemplation on all the living and non-living things was required as part of a monk’s Bhav meditation or Dhyan

The third line from the bottom highlights the five senses of the various living beings which need to be controlled. They are Soindi – Shrut or hearing, Charindi - Sight, Dhainidi- Smell, Rasinidi- Taste and lastly Fasindi- Touch. The fourth line from the bottom mentions the four sangnas which are Ahar (food), Bhaya (fear), Maithun (sex), and Parigraha (greed). The fifth line from the bottom mentions the three ways through which we bind Karma: Mana (mind), Vachan (speech), and Kaya (body). The top line indicates Karans or activities and states that such actions of mind, body, and speech should not be done by one, should not be done through others, nor should such actions be appreciated (anumodana). Right conduct or Samyak Charitra involves the control of mind, body and speech, five senses, four desires, protection of all living and non-living things, and at all times practicing the ten virtues of Jain Religion and meditating on various concepts of Jainism. Such a behavior leads to supreme Dhyan entitling the Jain monks to become a Bhav Saman and swiftly ride on the jewels of his Right Conduct and progress on the path of salvation, aided by his austerities. Haribhadra elaborates the calculations in (Fig 4), as follows: 10 Virtues of Dharma x 10 Categories of Jiva and Ajiva x 5 Indriyas x 4 Sangna x 3 Yoga x 3 Karans =18000 (10*10*5*4*3*3 =18000) and states clearly the number 18000 in Gatha 646 and 647 (Fig 4).The stated 18000 Shilang calculation by Haribhadra is explained in the table Fig 8 below: Calculating from the bottom:

1. 10 types of Dharma (Virtues of Religion) with permutation value of 1 for each type.

2. 10 types of Jiva and Ajiva (Living and Non-Living) are shown. Total permutation value of 10 types of Dharma from the previous line is brought forward in each box as 10*1 = 10.

3. 5 Indriya (senses) are shown. Combined permutation values of 10 Dharma and 10 types of Jiva and Ajiv in line 2 result in 10*10 = 100 and is brought forward in each box.

4. 4 Sangna (desires) are shown and the resulting permutation from line 3 is 5 (Indriya)*100 = 500 and is shown in each box.

5. 3 Yoga (Mind, Speech, Body) are shown. Resulting permutation values in line 4 is calculated and brought forward as 4 (Sangna) * 500 = 2000.

6. 3 Karan (Actions to Avoid) are indicated and the resulting permutation values for line 5 in each box is brought forward as 3 (Yoga) * 2000 = 6000.

Adding the 3 kinds of Karan (Actions to avoid) with its resulting permutation brought forward totals to 6000*3 = 18000. Hence, we derive the value of 18000 in the Shilang RathJinbhadra in his Dhyan Shatak, composed earlier than Panchashak, mentions

how a Sadhu can get on a boat full of Shilang (Right conduct) to cross the ocean of life (Fig. 4, Shloka 60) and reach the city of Nirvan, which is shown in the painting here as getting on a chariot of jewels of Shilang (Right Conduct) to quickly reach the city of Nirvan.

Similar figurative paintings explaining various Jain concepts are widely seen around the time of Acharya Srichandra (1136 CE), 6 the author of Sangrahni Ratna Srichandra’s Sangrahni Ratna is a concise version of Jinbhadra’s Sangrahn i. A folio from a copy of Srichandra’s manuscript done in 17th century is available in the British Library and is shown below in Fig 9.

The museum identifies the timing as 1400-1450 CE, which is possible, as it is later than the period of Acharya Srichandra of the 12th century CE whose Sangrahniratna is based on Sangrahani by Jinbhadra (6th-7th century CE). Collections at Victoria and Albert Museum show more information on Sangrahanratna related to Acharya Srichandra and connect it to Acharya Jinbhadra Gani, as the physical description states: “The work is also named at the end as the Trailokya dipi which is more usually applied to the Sangrahani Sutra of Jinbhadra Gani, the earliest work of this class.” Robert J Del Bonta further clarifies that Srichandra’s Sangrahani Ratna is the most illustrated of various Sangrahani Sutra and many of these illustrations are available in private and public collections across the world, mostly found in loose leaf 7

Hence, in conclusion, the painting of Chariot composed of Calculations from an unindentified Jain manuscript at the Asian Art Museum, San Francisco depicts 18000 Shilang Rath, based on the Jain manuscript Panchashak by Acharya Haribhadra Suri of 8th century CE. The painting is dated to 1400-1440 CE by the museum and is possibly a copy of an illustration around 12th century CE and is a folio from illustrations related to Sangrahani texts.

The above artwork emphasizes the need to carefully collate the details about the various Granths existing in the various Gyan Bhandars in the Jain temples across India. Preserving and digitizing such priceless manuscripts should be an important activity that needs to be supported by the Jain community. Also, I hope through this article, I have been able to bring to light the details and history of the hitherto unknown artwork, and that the information is found useful to be shared with the visitors and viewers at the Asian Art Museum, San Francisco. I thank the museum for showcasing this beautiful painting and for reaching out to its visitors for more information.

The author is immensely grateful to the Asian Art Museum, San Francisco, for graciously allowing free usage of the licensed image. The author would also like to show immense gratitude to the learned Dr Jitendra Shah of Shrut Ratnakar Trust for a valuable discussion on this artwork. View the Asian Art Museum collection

6 Sangrahani Sutra at Victoria and Albert Museum, UK

7 Robert J. Del Bonta CoJS Newletter March 2013, Issue 8 Pg 47-49

Fig. 9