Council of Architecture (COA)

www.coa.gov.in

The COA has been constituted by the Government of India to provide for registration of architects, standards of education, recognized qualifications and standards of practice to be complied with by the practising architects. The COA is charged with the responsibility to regulate the education and practice of the profession throughout India besides maintaining the register of architects.

National Institute of Advanced Studies in Architecture (NIASA)

www.niasa.org

(Academic Unit of Council of Architecture)

NIASA, instituted in July 2005, is a national level institute of excellence that facilitates research and training in various fields of architecture, to teachers of architecture, professionals, individuals and students. Set to grow in function and stature as per the growing demands of studies in architecture, NIASA presently operates in areas of research, teachers’ training, continuing education, publications, awards and aptitude testing.

CONCEPTSOFSPACE IN TRADITIONALINDIANARCHITECTURE

1

CONCEPTSOFSPACE IN TRADITIONALINDIANARCHITECTURE

Yatin Pandya

Y ATIN P ANDYA

Vastu-Shilpa Foundation for Studies and Research in Environmental Design

M APIN P UBLISHING

Mapin Publishing

First published in India in 2005 by Mapin Publishing Pvt. Ltd.

Ahmedabad 380013 India

Reprint in 2023 by Mapin Publishing Pvt. Ltd

Tel: 91-79-2755-1833 / 2755-1793 • Fax: 2755-0955

email: mapin@icenet.net • www.mapinpub.com

706 Kaivanna, Panchvati, Ellisbridge Ahmedabad 380006 INDIA

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

T: +91 79 40 228 228 • F: +91 79 40 228 201

Simultaneously published in the United States of America in 2005 by Grantha Corporation

E: mapin@mapinpub.com • www.mapinpub.com

77 Daniele Drive, Hidden Meadows Ocean Township, NJ 07712

© Mapin Publishing 2005, 2014, 2015, 2016

email: mapinpub@aol.com

Text and photographs by Yatin Pandya

Distributed in North America by Antique Collectors’ Club

Unlocking and interpreting the numerous folds of existence in this land of immensity and extremities has been an intense journey through time and space, where many individuals, events and experiences have knowingly or unknowingly helped in reinforcing convictions and traversing the unknown–some by walking together, and some by confronting the path with questions.

East Works, 116 Pleasant Street, Suite 60B

Easthampton, MA 01027

Tel: 800-252-5231

email: info@antiquecc.com • www.antiquecc.com

Text and photographs © Vastu–Shilpa Foundation for Studies and Research in Environmental Design and Yatin Pandya Drawings and Architectural Graphics © Vastu–Shilpa Foundation for Studies and Research in Environmental Design unless otherwise noted.

Distributed in the United Kingdom, Europe and the Middle East by Art Books International Ltd.

Vastu-Shilpa Foundation for Studies and Research in Environmental Design

‘Sangath’, Thaltej Road, Ahmedabad 380 054

Unit 200 (a), The Blackfriars Foundry

156 Blackfriars Road

While having been born in India has contributed by means of inheriting my ways of life and imbibing its subtleties, my journeys to other lands must have provided the neutral outlook to perceive the same objectively. Commitments towards teaching and academics may have forced one to question the fundamentals and not take things for granted, while the association with the Vastu-Shilpa Foundation gave the rigour and reason for the research.

London, SE1 8EN UK

Tel: 44 (0) 207 953 7271 • Fax: 44 (0) 207 953 8547

email: sales@art-bks.com

Distributed in South-East Asia by Paragon Asia Co. Ltd., 687 Taksin Road, Bukkalo

All rights reserved under international copyright conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any other information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Thonburi, Bangkok 10600 Thailand

Tel: 662-877-7755• Fax: 662-468-9636

email: rapeepan@paragonasia.com

The moral rights of Yatin Pandya as the author of this work are asserted.

ISBN: 978-81-89995-75-1

Distributed in rest of the world by Mapin Publishing Pvt. Ltd.

Edited by: Carmen Kagal

Design by: Jalp Lakhia / Mapin Design Studio

Draft layout: Pranali Parikh and Yatin Pandya

Separations: Reproscan, Mumbai Printed at Thomson Press (India) Ltd.

Text and Photographs © Yatin Pandya unless otherwise noted Drawings and Architectural Graphics © Yatin Pandya and Vastu-Shilpa Foundation for Studies and Research in Environmental Design

‘Sangath,’ Thaltej Road, Ahmedabad 380 054

All rights reserved under international copyright conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any other information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

ISBN: 81-88204-26-9 (Mapin)

ISBN: 1-890206-62-8 (Grantha)

LC: 2003113007

Edited by: Carmen Kagal

Design by: Jalp Lakhia / Mapin Design Studio

Draft layout: Pranali Parikh and Yatin Pandya

Separations: Reproscan, Mumbai

Printed: Tien Wah Press, Singapore

Frontispiece: The different architectural elements and the varying intensity of light at the Adalaj Stepwell, near Ahmedabad, comprise an arresting ensemble of vignettes.

The seeds of the enquiry were sown initially during the discussions for Pranali Parikh’s undergraduate research dissertation on "Hindu Notions of Space Making". She has been associated with the project all along, since then, through phases of research, graphics as well as layout. Dilip Karpoor joined in, and his questioning and reasoning helped generate debate and conviction of ideas. His contribution has also extended to editing the text through numerous rounds and drafting the initial text on the spatial sequences of Ellora. Raajesh Moothan and Ashka Naik’s help in the refinement of the final draft added finesse.

Pranali’s miniature style drawing and architectural graphics, Smita Gupta and Ashka Naik’s colour rendering of them as well as Priyamwada Singh’s freehand sketches for the spatial sequences provided able visual support to the text. Stephan and Rolf took the initial steps towards digitising the drawings for Adalaj and Modhera. The Maharana Mewar Charitable Foundation Project Management Office provided the base drawings for the City Palace, Udaipur.

Joseph Verughese’s help with typing, data organization as well as administrative aspects brought about the physicality of the document. Finally, it is only due to the total freedom of work environment at the Vastu-Shilpa Foundation and the unstinting support of Mr. Balkrishna Doshi that a casual enquiry blossomed into a formal study. This research has been undertaken at and is fully suported by the Vastu-Shilpa Foundation for Studies and Research in Environmental Design.

The journey continues, events keep unfolding, and I must thank Riddhi, my family and all others for travelling with me.

Yatin Pandya

4

CONTENTS I NTERPRETATION 008 A PPLICATION 036 I NFERENCE 134 G LOSSARY 147 R EFERENCES 148 R UDABAI S TEPWELL ADALAJ 38 K AILASH T EMPLE ELLORA 56 S UN T EMPLE MODHERA 78 C ITY PALACE UDAIPUR 98 S ARKHEJ R AUZA AHMEDABAD 116 I nterpretat I on 8 a ppl I cat I on 36 I nference 134 G lossary r eferences 148

urvey of India maps with the permission of the Surveyor General of India. di Su Based upon Su asedB ed up ed u d Publishing. Responsibility for the correctness of internal details shown on the main m n map rests with the publis ap publisher ests publisher. n she pin ©2013 Mapin Map 2013 M 013 3 MANIPUR ASSAM MEGHALAYA SIKKIM WEST BENGAL JHARKHAND BIHAR UTTAR PRADESH MADHYA PRADESH CHHATTISGARH MAHARASHTRA GUJARAT INDIA RAJASTHAN HARYANA PUNJAB UTTARAKHAND HIMACHAL PRADESH JAMMU & KASHMIR ANDHRA PRADESH KARNATAKA GOA TAMIL NADU KERALA ORISSA ARUNACHAL PRADESH NAGALAND MIZORAM TRIPURA A N D A M A N A N D N I C O B A R ISL ANDS LAKSHADWEEP H I M A L A Y A New Delhi Mumbai Hyderabad Gandhinagar Bhopal Panaji Bangalore Chennai Jaipur Patna Ranchi Bhubaneswar Raipur Kolkata Agartala Imphal Kohima Dehradun Chandigarh Simla Jammu Srinagar Shillong Guwahati Itanagar Aizawl Port Blair Gangtok Lucknow Modhera Patan Udaipur Dungarpur Khajuraho Fatehpur Sikri Agra Datia Adalaj Ahmedabad Muli Ellora Elephanta Mandu Hampi Pattadakal Srirangam Chidambaram Kanchipuram Jaisalmer Madurai Thiruvananthapuram Places mentioned in the book

PREFACE

What makes historic architecture awe-inspiring?

Why is it that even after centuries and millennia, despite functional obsolescence, these architectural masterpieces have retained their vitality?

What spatial qualities and organizational principles have rendered them timeless?

Can these qualities be deciphered and reinstated in contemporary times?

These questions become immensely pertinent in the Indian context due to its rich heritage and age-old traditions. In India, we live in three time zones simultaneously. The moorings of the past and aspirations for the future combine with the realities of the present, through an alchemy of conditioning over the millennia. Here, in India, the past continues as living tradition, both relevant and valid for the present.

The manifestation of an idea, architecture is a celebration of life. From philosophy and rituals to art forms and architecture, all are extensions of a way of life, echoing the underpinning notions of the Indian context. Any projections founded on the fundamental philosophical and ideological tenets of the place and people are therefore sustainable and timeless.

History is a function of time and space. Materials, construction techniques, style and ‘isms’ are conditioned by the context. Even form and scale are dividends of conditioned learning but the eventual experience is eternal, humanly universal and intuitive. Experiential richness and the ability to identify with pluralistic value systems are the hallmarks of timeless architecture. Traditional Indian architecture has ably demonstrated the universality of its communication as well as its validity within multiple value systems. This is achieved essentially by relying on spatial experiences derived through narratives–dynamic perception of space while in motion–its kinesthetics. The interactive process of encoding and decoding between the space and the perceiver orchestrates spatial narratives.

This research is an attempt at understanding the very roots of what constitutes the Indian context by examining its notions of time, space and existence. Deciphering their implications on the physically manifest, the study unravels the inherent virtues of traditional Indian architecture and interprets them as universal dictums, relevant to reinstate in contemporary times.

Yatin Pandya

7

I NTERPRETATION

8

9

S PATIALNARRATIVESINTRADITIONALINDIANARCHITECTURE –A NINTERPRETATIONOFACONCEPTFORCONTEMPORARYRELEVANCE

H ISTORYVERSUS T RADITION P RESENTASTHE L IVING PAST

India! The land of antiquity. Its heritage is not confined to historic accounts of events and objects frozen in their own time and space, but is perpetuated as cultural and architectural traditions, which have transcended time and space to remain alive and appropriate even in the present. In India, history stays alive as living tradition. History and tradition both have their roots in the past, but history, for its inability to adapt to the changed time, is rendered obsolete as fossilized remains of a bygone era. Tradition, on the other hand, consistently adapts and suitably transforms to changed circumstances. This process of constant updation makes tradition survive and renders it timeless. It survived the past and promises to prevail in the future as it rests on collective concurrence, shared values and deep-rooted conditioning. Thus, tradition–as living heritage–retains its contemporariness and relevance even for the present times. In India, the people simultaneously live in three time zones. The legacies of the past and aspirations for the future effectively combine with the realities of the present.

10

1

1: Cultural associations and shared values keep monuments alive as living history, as at the Taj Mahal.

2: Tradition stays alive as the living past, as signified by a tajia procession during the Moharram festival.

3: Chimneys, historically the symbols of industrial prosperity but now obsolete in a changed time, lose their significance and are eliminated.

4: Traditionalism does not imply turning the clock backward. On the contrary, it is a progressive and consistent process of updation that subtly combines the ‘old’ with the ‘new.’ Seen here is a creative fusion of day-to-day utensils in the form of a deity, Ganesha.

11 2 3 4

DYNAMICSOF

XISTENCE

Time, in the Indian psyche, is a cyclic phenomenon. The faith in reincarnation, the cycle of birth, death and rebirth, the unending chain of construction, destruction and reconstruction, all reaffirm the belief in the recurrence of time. This assurance of recurrence instills a sense of equality as well as hope, much needed qualities in the pluralistic context with diverse value systems. However, although cyclic, time is not static. It is helical, evolving continuously. The concept of change is inexorably tied to the concept of time. The past and future are distinct domains in the continuum of time within which change occurs as a sequential series of events. The processes of evolution, involution and devolution go on constantly. What is of importance is that the progression is not as a linear continuity but as a helix or a spiral with a still centre and a dynamic periphery.

1: Nataraja, a classical form of the Lord Shiva immersed in Tandava Nritya, literally, the furious dance of destruction grieving the death of his wife Sati. It depicts a dynamic balance between creation, destruction and reconstruction, as symbolized here by the presence of the damru, a sort of drum, the ring of fire, the demon below, and the reassuring blessing open hand gesture respectively.

2: The cyclic process is also depicted in the Dashavatara, the ten incarnations of Lord Vishnu, where even the supreme divine is not spared the cycle of birth, death and rebirth.

2: The cyclic notion of time is also evident in the concept of ten incarnations of Lord Vishnu. This cycle is a helical path. The incarnated forms from Fish to Amphibian to Animal to Half Man-Half Animal to Child to Adult define evolution of life within the cycles of time.

3: Time through the ages has been conceptualized as a cyclic phenomenon. The Puranas, ancient scriptures, have personified time in the form of a Kalapurusha, whose form in itself symbolises its cyclic nature.

3: Time through the ages has been conceptualized as a cyclic phenomenon. The Puranas, ancient scriptures, have personified time in the form of a Kalapurusha, whose form in itself symbolises its cyclic nature.

12

Matsyavatara Kurmavatara

Ramavatara Buddhavatara Kalkiavatara Parshuramavatara

1 3 2

E

T HE A LCHEMYOF T IMEOVER S PACE

Krishnavatara

Narsimhavatara Vamanavatara Varahavatara

While time may recur, the alchemy of time with space renders the resolute always unique. For example, at any given time different spaces render themselves differently for an obvious reason–their physicality. Likewise the same physical space transforms drastically through its interaction with time. Therefore, having invested in time, the spaces change, rendering them vital, vibrant and dynamic. This constant juxtaposition of time over space is the essential premise of Indian architecture. This is a creative resolution under scarce resource conditions. A builtform, however complex, once realized, remains static. However, if made to interact with nature, the interface is always dynamic. The sun is not the same from morning to evening or from one season to another. Thus, direction, light intensity and shadow patterns changing all the time constantly redefine the builtform making it feel different and thereby alive. Thus, in the space-time chemistry, apart from the space dynamics, time also interacts actively to condition the mind and create a familiarity with the built object.

This aspect of time in architecture is introduced through structured movement. Movement exalts to become the key to spatial perception. Traditional Indian architecture is the story of movement and pauses where the kinesthetics of a space is fundamental to its experience and perception. The layering, movement corridors, thresholds and circumambulatory are aspects of this phenomenon in Indian architecture.

The diurnal metamorphosis of a traditional urban square, Manek Chowk, Ahmedabad, where spaces change radically over time: The square is a cow-grazing ground in the early mornings, where people collectively feed grass to the cattle. The same square becomes a platform for daily chores and is also used as a playground just before business hours. Through the day it converts into an intense business district with shops, hawkers, people and parking. Late evening through night, the square transforms into an outdoor eatery. Thus the same physical space is rendered different over time. This is an efficient optimization of space resources through the overlaid matrix of time.

4: Early morning–6:00 a.m. to 8:00 a.m.

5: Business hours–9:00 a.m. to 8:00 p.m.

6: Late evening–9:00 p.m. to 1:00 a.m.

13 4 5 6

D UALITYOF E XISTENCE W ORLDWITHINAWORLD

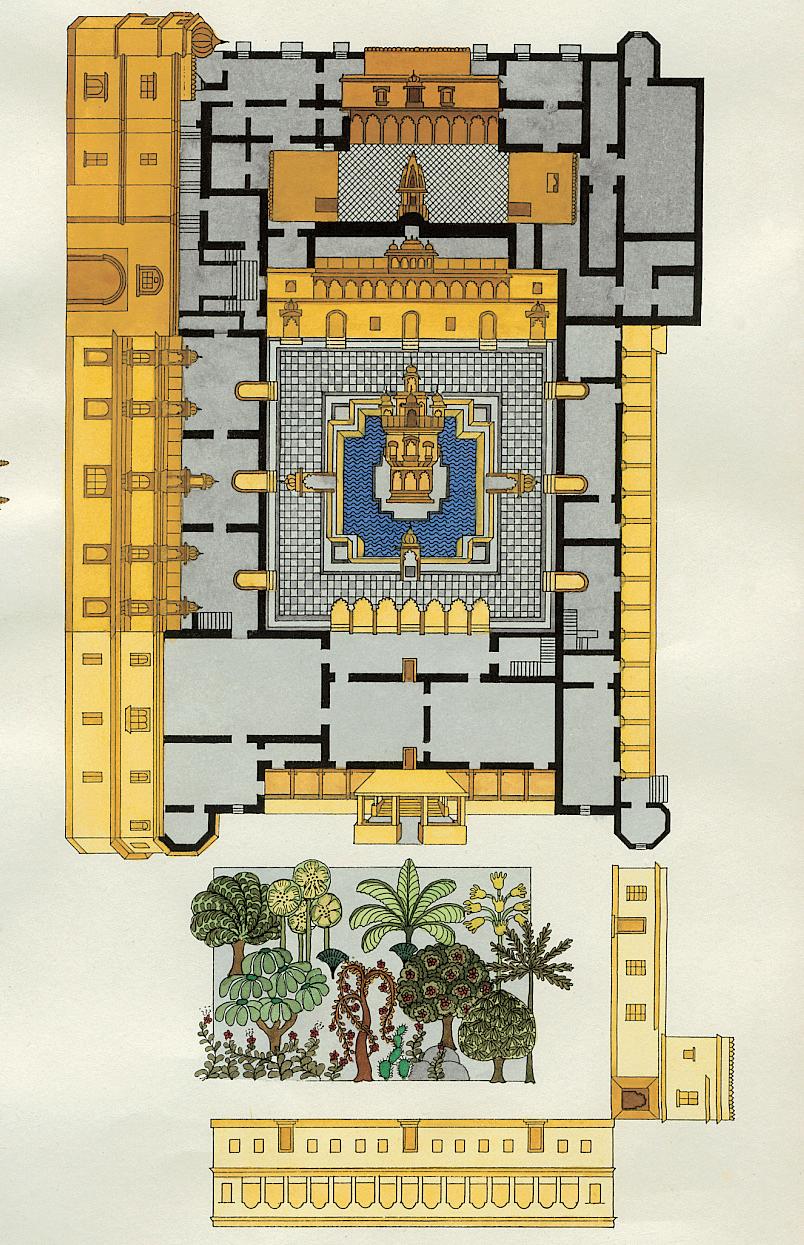

The Indian notion of existence rests on dualities. Atman, the infinitesmal building blocks of the human spirit, and Brahman, the overall schema of the universe, are the fundamental basis of any existence. This schema of dual existence simultaneously accepts the part as a whole and the whole as a part and gives rise to the concept of the ‘world within a world.’ Each entity is complete in itself at one plane and yet, at the other, is part of a larger system. A microcosm within a cosmos. This ensures freedom of individual expression, yet within the collective consensus. Of an identity within conformity. An effective tool to accommodate diversity while respecting the common bond of unity. This is critically required in a pluralistic society with multiple value systems. Individual belief systems must be accommodated, while the common code of understanding also needs to be maintained. This balance is finely arrived at through this notion of centres and sub-centres. Courtyards creating a world within a world and the schema of structure and infill, which bring out subtle variations within unified expressions, are obvious translations of these notions in architecture.

The courtyard is a characteristic device of Indian architecture that is most effective in creating a world within a world. The courtyard surrounded by the built mass creates an introverted response. Becoming a focus in itself, it allows for activities to spill into it and thrive without being disturbed by external conditions.

This element has been effectively used in designing royal campuses, palaces or even residences with different activities conforming to functions in multiple courtyards, where varying privacy gradients are respected in the form of a clearly delineated hierarchy of courts.

1: A biological cell, like an atom, believed to be the building block of the body, is still a complex, complete entity in itself.

2: India has a pantheon of around 330 million gods. This concept of many gods accepts the notion of many truths, each right for its believer, rather than a dictatorial structure that imposes a single truth. An effective concept to nurture the diverse notions of a pluralistic society.

3: A miniature style painting depicts the Ras-lila, a dance form adoring Lord Krishna, where each gopi, a devotee of the Lord, is under the illusion that she is dancing with him. Each one reaches out to the ultimate centre through one’s own locus.

Source courtesy: Amit Ambalal

4: Contained yet open to nature, courtyards are a complete world in themselves supporting varied forms of human activity. A haveli or large residential mansion at Muli, Gujarat.

5: The ‘world within a world’ concept is manifested through yet another typology with a non-centric approach as seen in the Jagnivas Palace in Udaipur. Here courtyards are interlinked by corridors to form a flexible structure and each courtyard retains its individuality through its own scale and shape, yet complementing the overall schema of the space organization.

14 1 1 2 3

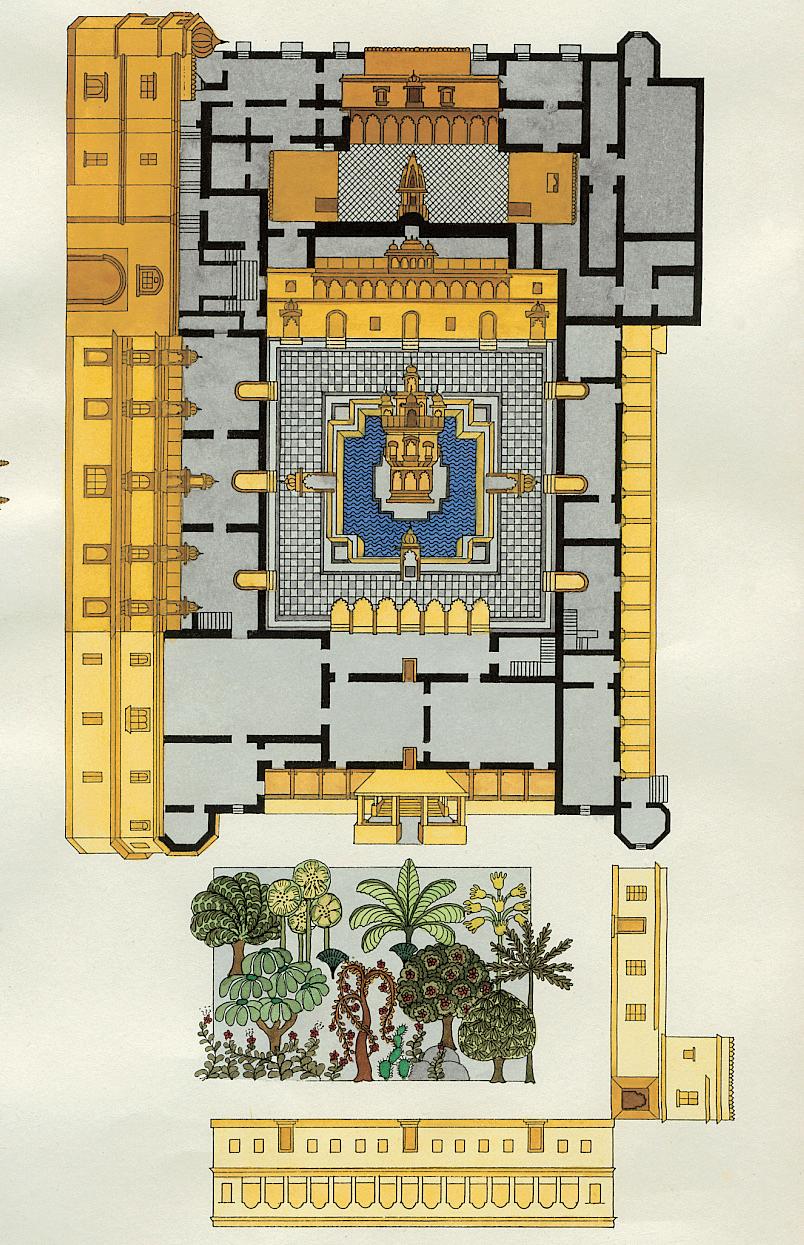

6: The Udai Bilas palace at Dungarpur creates different moods through its multiple court structure such as the vegetated garden-like forecourt, harem court with free-standing mirrored pavilion and the sacred innermost court with a shrine. A miniature painting style impression.

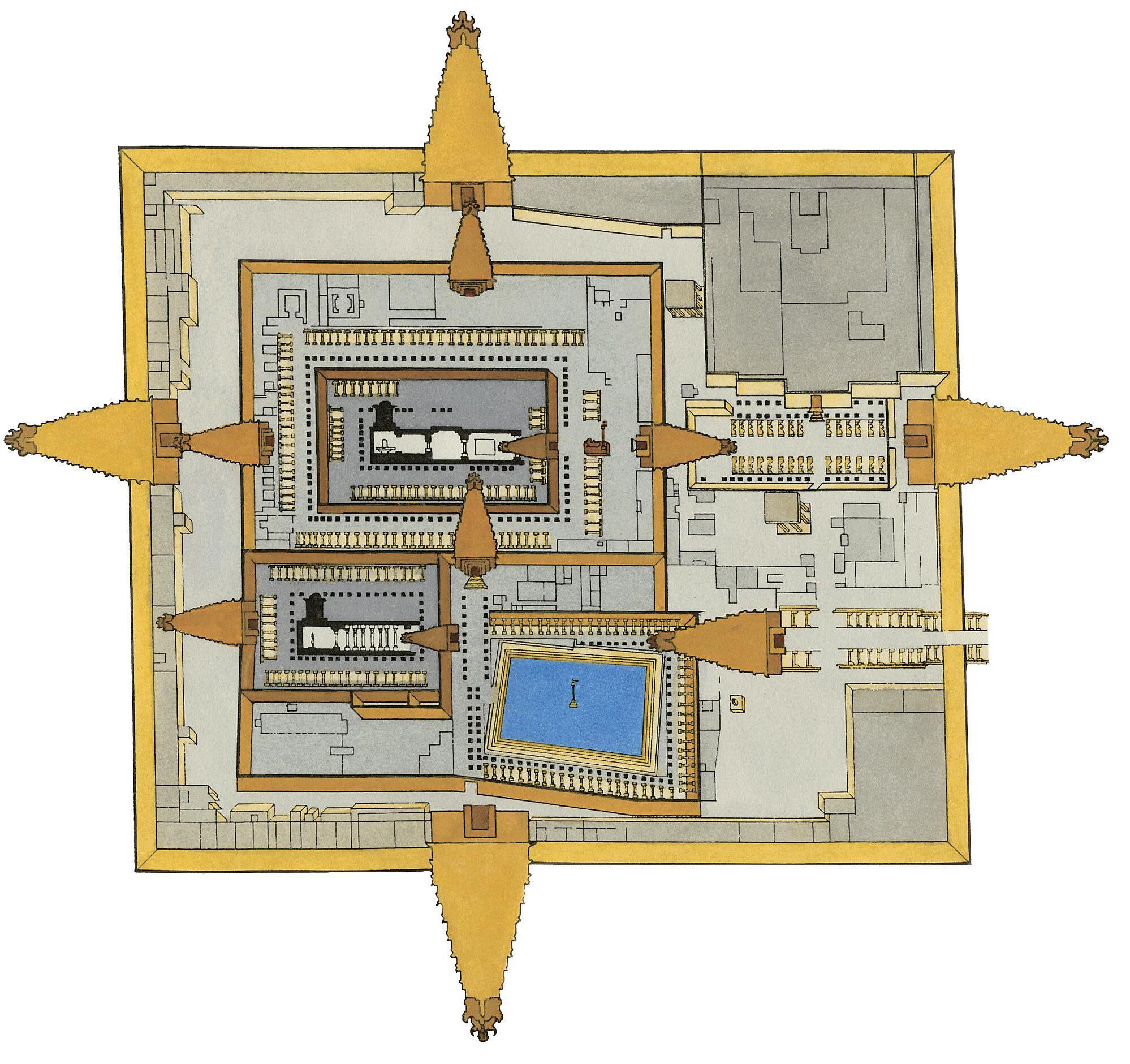

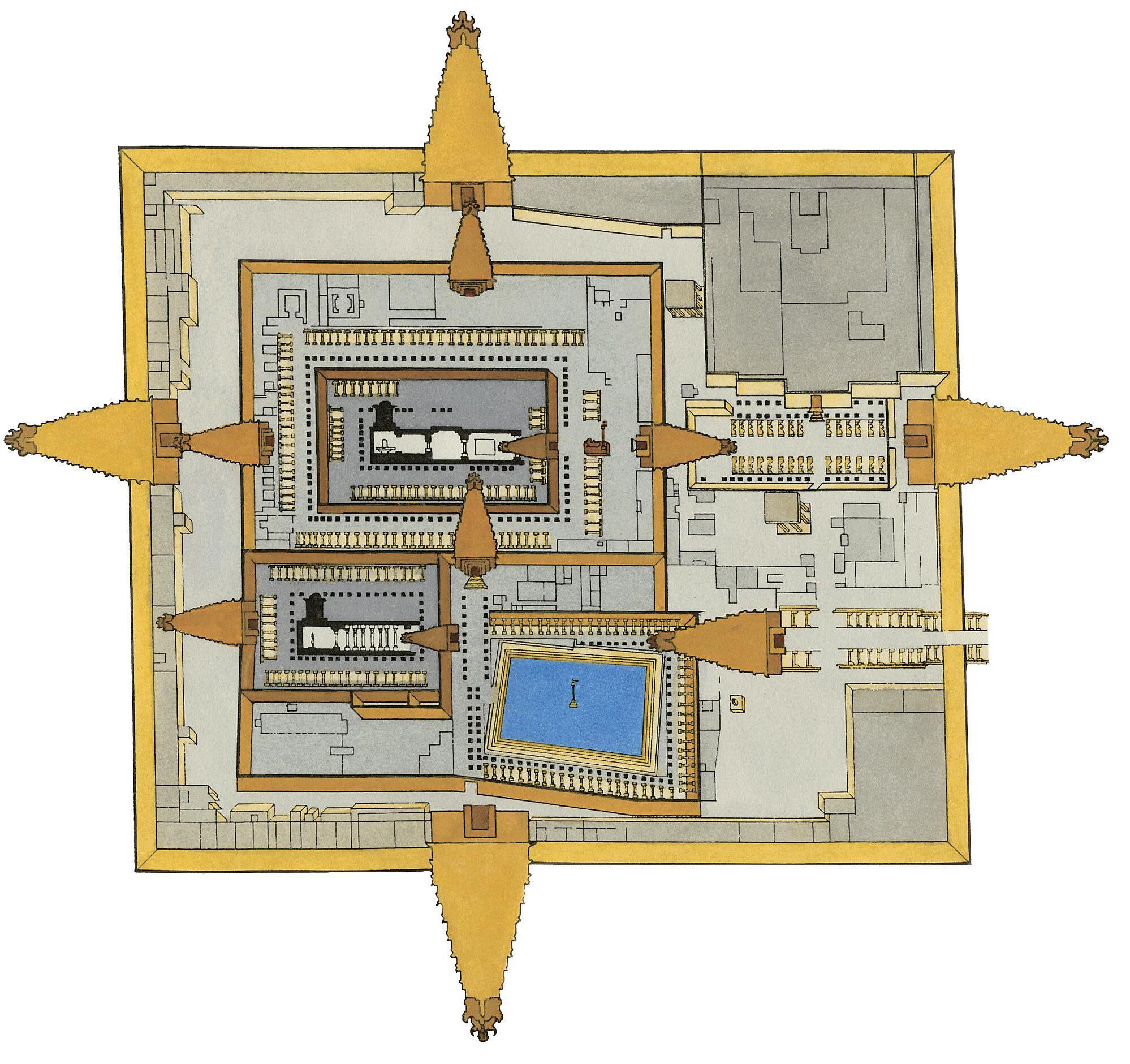

7: The Jambukeshwara Temple in the temple-town of Srirangam, in southern India, quite aptly demonstrates the concept of a ‘world within a world’ through concentric layering of walls and gates, where each subsequent layer gets more and more secured, sacred and withdrawn from worldly affairs, thus achieving a gradual transition from the corporeal to the celestial.

15 4 5 6 7

7: The Ranganatha Temple in the temple-town of

D UALITYOF E XISTENCE PARTASAWHOLEAND THEWHOLEASAPART

Understanding and acceptance of the duality of existence, where the part-to-whole relationship is not a hierarchical structure but a symbiotic one, gives in the overall schema of existence each component and each ingredient under it the freedom to exist, function as well as express itself independently. The collective resolution, however, still remains a chemistry of all the sub-components.

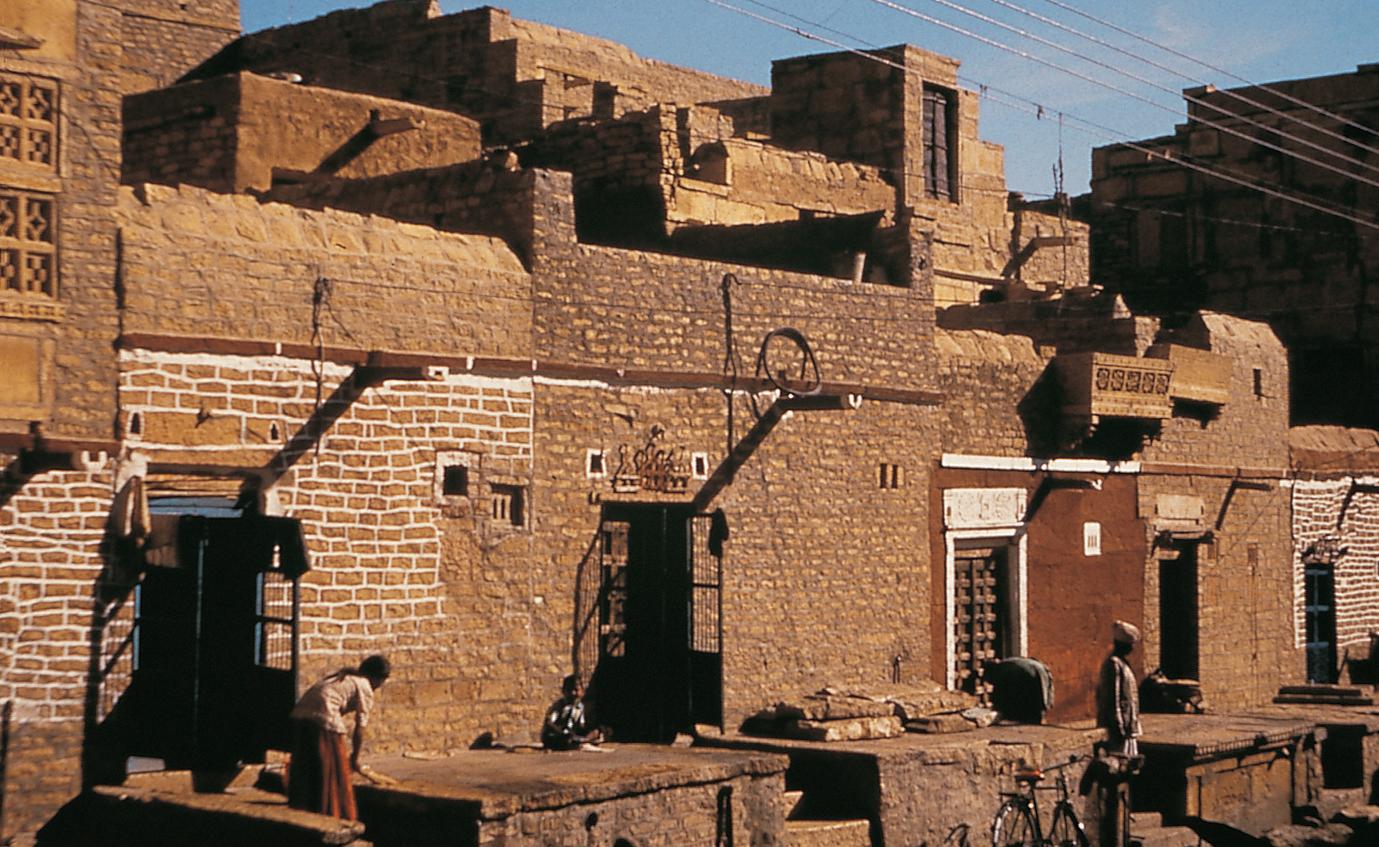

The same is expected of architecture. Streets of traditional towns best demonstrate this phenomenon. Streets get defined as a singular entity unified through zoning of fenestration, contiguity of the built edge as well as overall co-ordination of mass and scale. However, within this uniformity, identity is also respected and individuality is subtly expressed through freedom of choice, stylized elements, colours or innumerable gestures of personalization. These also help induce a sense of belonging without disrupting the overall harmony. The variation resultant of these inherent processes also helps break monotony and instill the overall with a rich sense of diversity.

1: Each individual is distinctly identifiable yet is a member of a clan, the society

1: Each individual is distinctly identifiable yet is a member of a clan, the society.

2: In Indian cuisine, a number of spices contribute to create a composite rasa, the resolute experience of taste. The absence of any one ingredient is readily perceptible, yet the composite essence is what matters.

2: In Indian cuisine, a number of spices contribute to create a composite rasa, the resolute experience of taste. The absence of any one ingredient is readily perceptible, yet the composite essence is what matters.

3 and 4: Bhungas, traditional circular adobe dwellings in Kutchchh, Gujarat, are distinct living spaces in themselvesyet form the basic unit of the homogeneous settlement form.

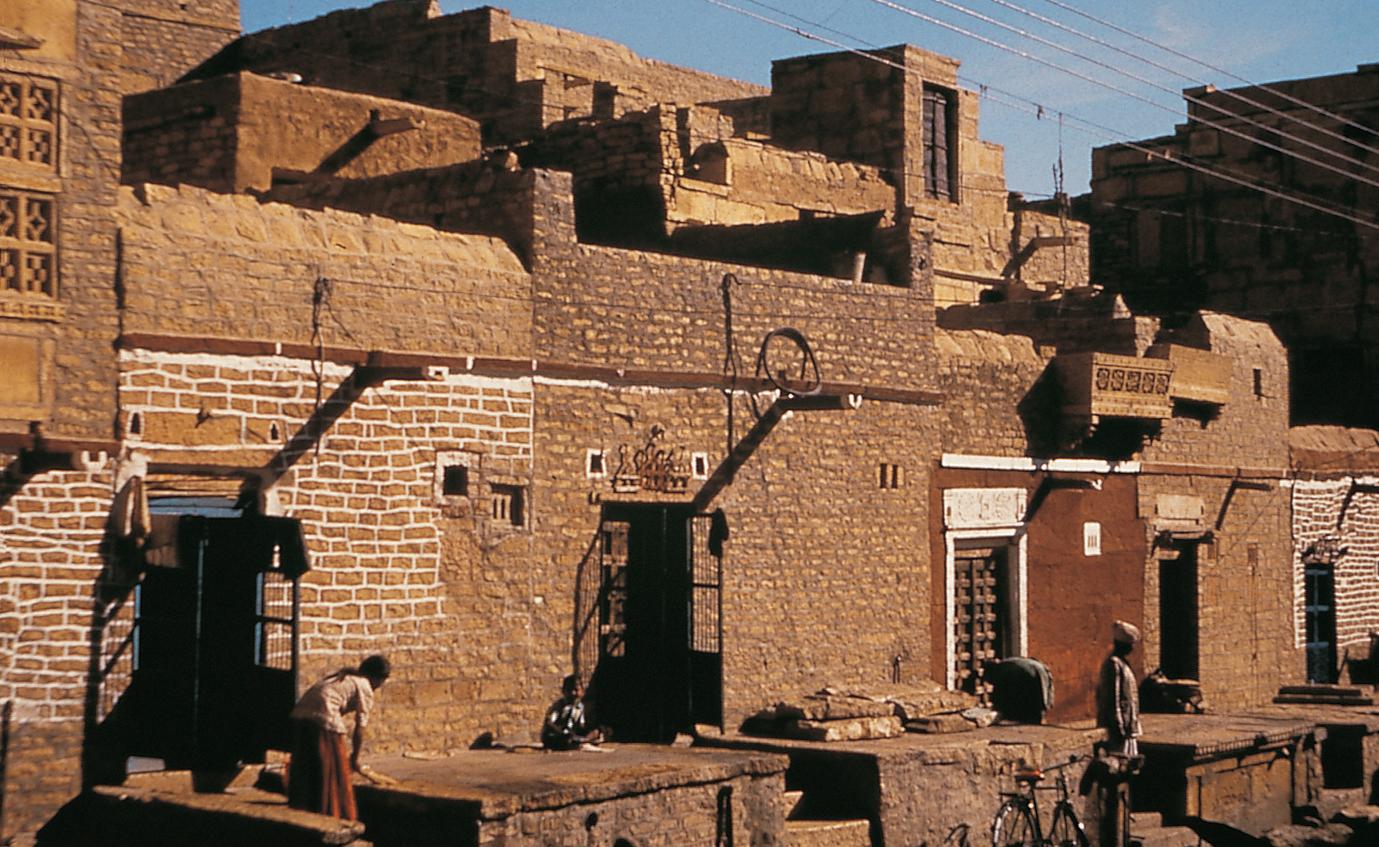

5: In Jaisalmer, identity within conformity is achieved by varied permutations and combinations of nearly modular elements, with continuity of built mass and harmony of scales.

Photo courtesy: Vikram Bhatt

6: At Jaipur, the arcades and continuous built mass act as binding factors, while the variety of openings and extensions provide variations.

3: Thali—the Indian food platter—as a phenomenon of combination meal epitomises Indian pluralism. It has pre-cooked, standardised, may be often mass-produced ingredients, even served the same way to all. But as a combination meal, it offers choices for permutation and combination. This makes each bite a unique experience. This also renders the thali as a personalised and unique experience as one is an active participant of the process. Two persons eating the same thali, despite the sameness of ingredients, do not share the same experience because the permutations, sequence and proportion remain unique to each person.

4: In Jaisalmer, identity within conformity is achieved by varied permutations and combinations of nearly modular elements, with continuity of built mass and harmony of scales.

Photo courtesy: Vikram Bhatt

5: At Jaipur, the arcades and continuous built mass act as binding factors, while the variety of openings and extensions provide variations.

7: Pols, the residential precincts of the traditional quarter of Ahmedabad, exhibit homogeneous heterogeneity through contiguous transition zones consisting of plinths, columns, jharokhas or balconies and chhajas or overhangs.

6: Pols, the residential precincts of the traditional quarter of Ahmedabad, exhibit homogeneous heterogeneity through contiguous transition zones consisting of plinths, columns, jharokhas or balconies and chhajas or overhangs.

16 1 2 4

3

17 5 6 7 4 5 6

B IPOLARITYOFEXISTENCE O PPOSITESASCOUNTERPOINTS

The aspect of counterpoints is built into the Indian notion of existence as bipolar, where opposites reinforce each other. May it be purusha (man) and prakriti (nature), light and darkness, or solid and void, they are the mutually defining aspects. One shapes and gives validity to the existence of the other. Hence, apparent extremes co-exist in India. As counterpoints they become mutual references and an integral part of a self-balancing system ensuring continuum and endurance. This form of lateral understanding thus allows for apparent opposites to co-exist.

Opposites in the Indian context are exemplified and portrayed through various means, but can be broadly typified into three categories. Definition through negation where mutual definition is achieved through absolute negation, of one while the other is presented in full glory followed immediately by a reversal of roles. A co-existence of extremes, where one can be experienced only due to the presence of the other and vice versa. Relative identity, where once the two opposites are understood and identified they are placed within a particular relation as a composition which, due to their relative nature, becomes a third entity not characterising either but with the collective import of both.

1: Ardhanarishwara, a Chola bronze depicting Lord Shiva in his androgynous form. A personification of the synergy of opposites dissolving and fusing into itself the characteristic features of the two lateral physiognomies. Existence lies between the two extremes. Courtesy: Government Museum, Chennai

2: Relative Identity/Co-existance of extremes/Defined through negation.

3: The Shiv-linga, a metaphorical depiction of Lord Shiva, is symbolized through the union of the male and the female genitals, the union of the purusha (male) and the prakriti (primeval matter identified with the female principle) bringing forth life and existence.

4: Arghya, the ritual of offering water to the sun, brings together the opposites in the palm through reflection. Fire and water, ether and earth, warm and cool–which in reality remain apart–all come together notionally.

18 1 3 2 4

The aspect of existence by negation is best exemplified in traditional Indian architecture through symbiosis of the built with the unbuiltmasses. Indian architecture often is the architecture of the unbuilt. The unbuilt is defined by the built while the built subsists through the unbuilt. The courtyard again is a key element in this regard. Culturally and climatically relevant, the activities extend into the enclosed area almost as outdoor rooms. Streets and courts are therefore the successful theatres of spontaneous activities.

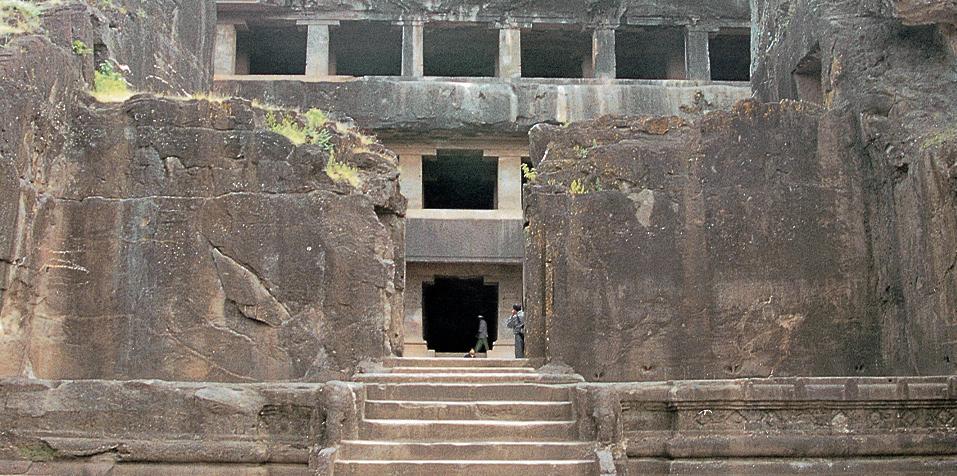

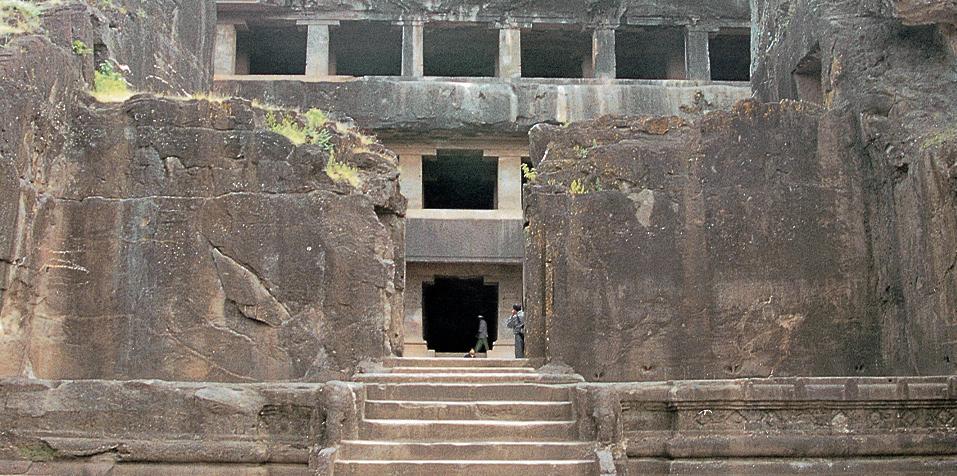

Cave temples are another apt example of this phenomenon of bipolar existence. The darkness of the cave helps appreciation of even a little source of light through courts, cracks and crevices. Caves also exhibit the coexistence of the raw with the finished–unfinished faces of the rock give meaning to the carved components. Juxtapositions of scooped-out spaces with the free-standing assembly also help substantiate each other mutually. The light crevices in cave temples, the court as a void within built-mass, water-bodies to reflect the sky, finished elements amidst raw surfaces, etc., are the juxtapositions in architecture reinforcing the sense of duality. Paradoxes prevail here, since, to an Indian psyche, notions rather than physical realities are more critical. ‘Space’ is a notional phenomenon, which shapes as well asexists by the context. Space-making is the sum total of the combination of time and space.

5: The City Palace, Udaipur, is a composition of built masses and voids where both proactively communicate with each other, contributing to the overall effect. Mass is registered due to the presence of void, while void is defined through mass.

6: Plasticity, roughness and monolithic masses are contrastingly juxtaposed with rectilinear, richly-carved columns at the cave temples as mutually referential.

7: Columns define the intercolumnation while the light does the shadow. The converse is as true.

8: Light gains meaning by its absence–cave temples, Ellora.

19 5 6 7 8

S PATIALNARRATIVES S ENSORIAL , EXPERIENTIALANDASSOCIATIONALPERCEPTION

Architecture is a celebration of life. The manifestation of an idea, it encodes messages and emotes feelings. Architecture communicates through spatial tools, whether they be the space sequences and their organization; elements of space-making and their scale and form; or the symbolism of surface articulation. It is this aspect of encoding and decoding that sets off an instantaneous dialogue between the user and the architectural product. The effectivity of the communication depends as much on the easy comprehension of the encoded messages as their appropriate compliance in builtform.

Communication takes place at three levels–sensorial, experiential and associational. Sensorial perception refers primarily to the physiological comforts accrued from physical resolution, essentially in response to environmental control. This bodily perception is humanly universal. The experiential aspect of communication is also universal, but the perception through this experience differs vastly as this aspect deals critically with the mental and emotional status of the perceiver. The process is spontaneous and reactionary to the nuances of space configuration and its dictates. The associational communication is a locale-specific perception requiring preconditioning and familiarity with the context or the acquired information base. It creates spiritual bonds and succeeds through in-depth understanding of cultural connotations.The complete communication occurs through a wholesome balance of all three.

In architecture, vision is the primary sense of perception. The inferred messages through perceived visual frames can guide and dictate behaviour. For example, a static, blank wall, with a curvature or inclination may guide the movement and, placed en-face as a baffle, may restrict it. This same wall, when overlaid with motifs and symbols, communicates further through associations that they may conjure. Such is the process of communication, where messages are encoded and decoded through an interactive visual process.

Architectural spaces can potentially nourish both emotionally and spiritually. A typical Hindu temple best illustrates this phenomenon. In the Hindu notion the act of prayer is very personal and a one-to-one connection is sought between the devotee and the deity. In order to facilitate such a notion the architecture of the temple must be complementary. In a temple, the sequence of gopurams (entrance gates), the series of ascending steps and platforms, the rising volumes of domes and shikharas or steeples, the increasing degree of enclosure, and the transition from the semi-open, multidirectional pavilions to the uni-directional dark sanctum enclosed by solid walls, all heighten the progression from the corporeal to the spiritual as one progresses from the gopuram to the garbhagriha or sanctum. This sense of transcendence from the worldly to the metaphysical,from the terrestrial to the celestial, from the matter to the mind is further enhanced by the culmination of the horizontal planes of the platform into a vertical axis through tall pointed shikharas symbolically reaching towards the heavens. In this manner, the elements of a building, its scale, size, volume, degrees of enclosure, levels of illumination as well as its motifs and decorations instill and evoke in the observer the ethos appropriate to the place.

Transcending time and space, good architecture remains communicative and interactive all the while through its spatial qualities. These spaces possess the qualities which establish a rapport with the perceivers and condition their perception even independent of their cultural backgrounds.

Timeless, ever-pervading architecture relies more on the fundamental attributes of space-making, ranging from approach and movement,scale and proportion, quality of light and shade to the relationship of the built with the unbuilt. These aspects are mostly qualitative and sometimes subjectively relative. Such architecture therefore needs to be understood and interpreted through perceptual and experiential qualities and not by the abstractions of the

plan geometry or static compositions of the facade elevations.

The visual dynamics of moving through the space and sensory perception of it is vital to wholesome architecture.

Kinesthetics, kinetic aesthetics, the dynamic perception of space through movement with ever-changing points of view and the varying vignettes resultant of the spatial composition, is the most fundamental facet of space-making in traditional Indian architecture. Time and again, the design of architectural masterpieces across the country, regardless of style, function or type, have been determined by this aspect of encoding narratives into their space organization, actively involving the perceiver, through the decoding process, in his journey through the space.

Space is conceived and perceived on the basis of movement through it. The journey, the process of moving through the space, in itself becomes the event. The clues for movement, inherent to the space, are revealed sequentially. The time gap required for the deconditioning of the previous and the preconditioning for the next is taken care of within the dimensions of the current space. This gradual unfolding of spaces creates a sense of curiosity within the visitor and involves them in the process.

Though the disposition of spaces is along the visual axis, the physical path of movement shifts to make the onlooker move around the notional centres of the space. Change in direction and diversion of movement cause variations in path and axis. Thus, axiality is characterized by variety. The whole length of the imperceptible axis is not revealed at once but is experienced as an episodic sequence of spaces. These sequences are deregularized by thresholds or pause elements. These elements not only create individual nodes of interest and enhance the pause in movement, but they also define spatial boundaries and reinforce the transition from one space to the other.

20

The transition from the corporeal to the celestial in a typical Indian temple is architecturally achieved through ascending plinths, rising shikharas, increasing degree of enclosure, decreasing intensity of light and the intimacy of the scale of space.

K INESTHETICSIN M EENAKSHI S UNDARESHWARA T EMPLE , M ADURAI , 15 TH –18 TH C ENTURIES

The temple complex of Madurai, built over phases, ably demonstrates such narratives within the space and takes the perceiver through the process of visual interactive communication. The gopuram–a tall entrance gateway–provides the visual reference from faraway distances. It acts as a magnet, arresting the vision and attracting one towards it. It conjures a notion of having entered the religious realm. Thus guidedby the gopuram, when one enters the gate, the subsequent layers of walls take over. The baffles in the form of wall planes and sculptural masses guiding one around these structures deflect the direct path of movement. The ritualistic circumambulation unassumingly becomes part of the movement. Each turn orients one to the shrines of sub-deities. A series of such foci and a sequence of colonnades slowly withdraws one from the corporal world and ushers him into the spiritual one. In this transition, the open colonnades gradually get more and more enclosed with increased presence of wall planes, as the sense of enclosure

1: A miniature style painting of the Meenakshi Temple at Madurai, fusing the plans, elevations and the movement paths.

2: Overall view of the Meenakshi Temple complex, where uni-centred but hierarchical, multi-layered organization with multiple linkages offers choices of paths to eventually culminate at the same core.

3: The towering gopurams–entrance gateways–as visual references and guiding magnets, attract movement towards entrances.

4: Decreasing light, increasing enclosure and intensifying iconography en route to the sanctum induce withdrawal from the external world.

5: Long corridors with larger than life depictions of grotesques, nymphs, gods and godesses gradually become darker with the ultimate focus brightly lit at the end. These guide the mind and the movement.

6: In the dark sanctum, in the absence of all sensory stimuli, the intuitive faculties overtake conditioned learning, allowing for an intimate one-to-one dialogue.

increases through the sabha (nritya) mandapa–pavilion for gatherings and dance–and the goodha mandapa–an antechamber to the deity’s sanctum. The intensity of light inversely decreases and becomes nearly negligible at the fully enclosed garbhagriha or sanctum. This is a dark space ideally occupied only by the deity and the devotee. The stone sculpture of the deity is revered as God.

Here notion plays a more important role than the physical manifestation of the entity. Form loses value and association is revered as the darkness renders nearly imperceptible the actual form of the idol and thereby suggests its inconsequentiality. It instead allows for

concentration of the mind, where the notions come through. Motifs and sculptures along the movement corridor also condition the mind while they too transform with increasing penetration into the precinct through depictions of royal stories to that of nymphs and apsaras (heavenly damsels) to gods and goddesses. Each baffle creates a pause to discover and reorient. The next set of clues gets unfolded at every subsequent pause, creating a sequential unfolding and a sense of discovery. This extended movement, adding the element of time over space, helps in the conditioning of the mind. This makes the journey both physically and mentally engaging and, thus, fulfilling.

22

1

23 3 54 6 2 4 3 6 5 N

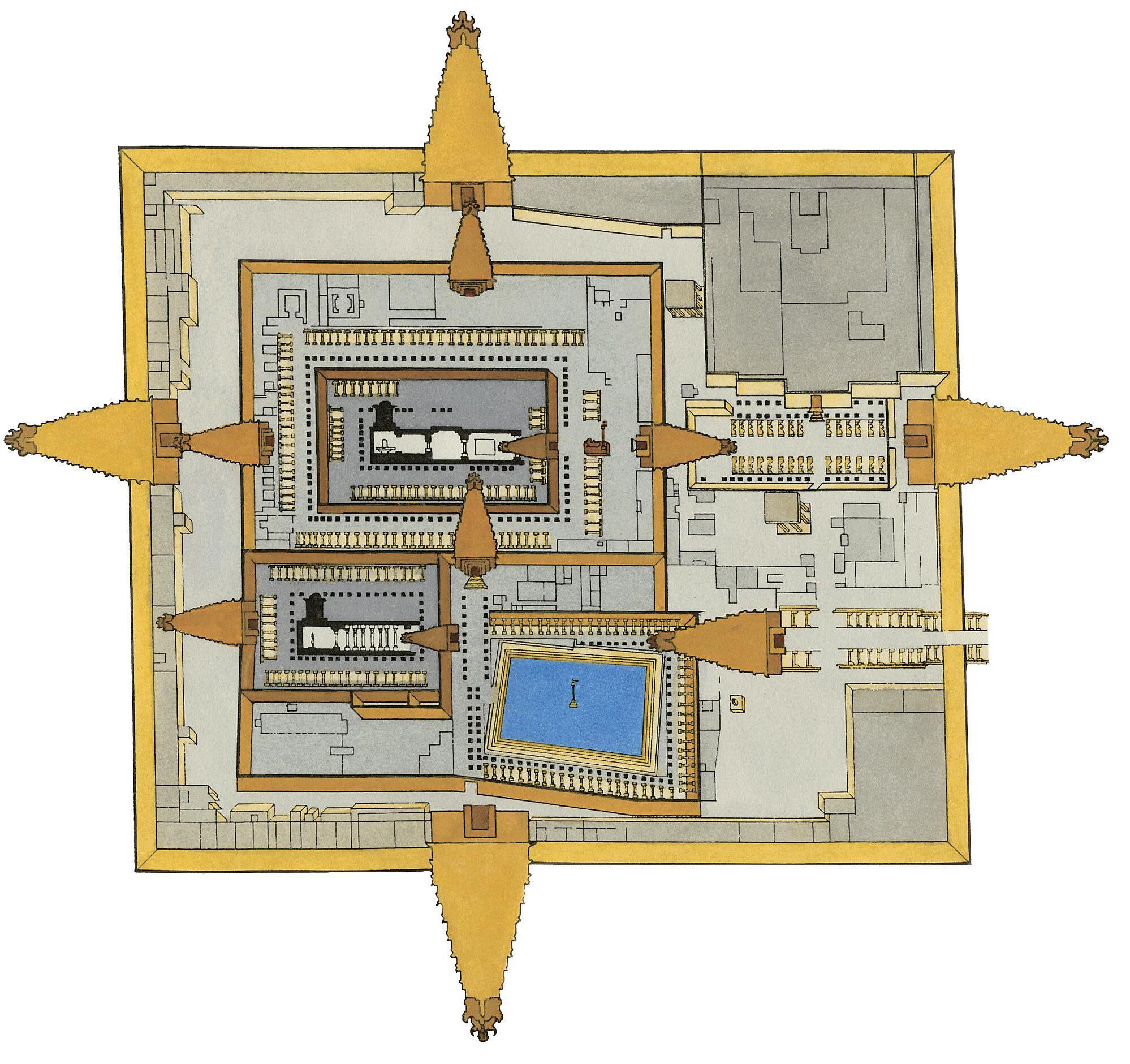

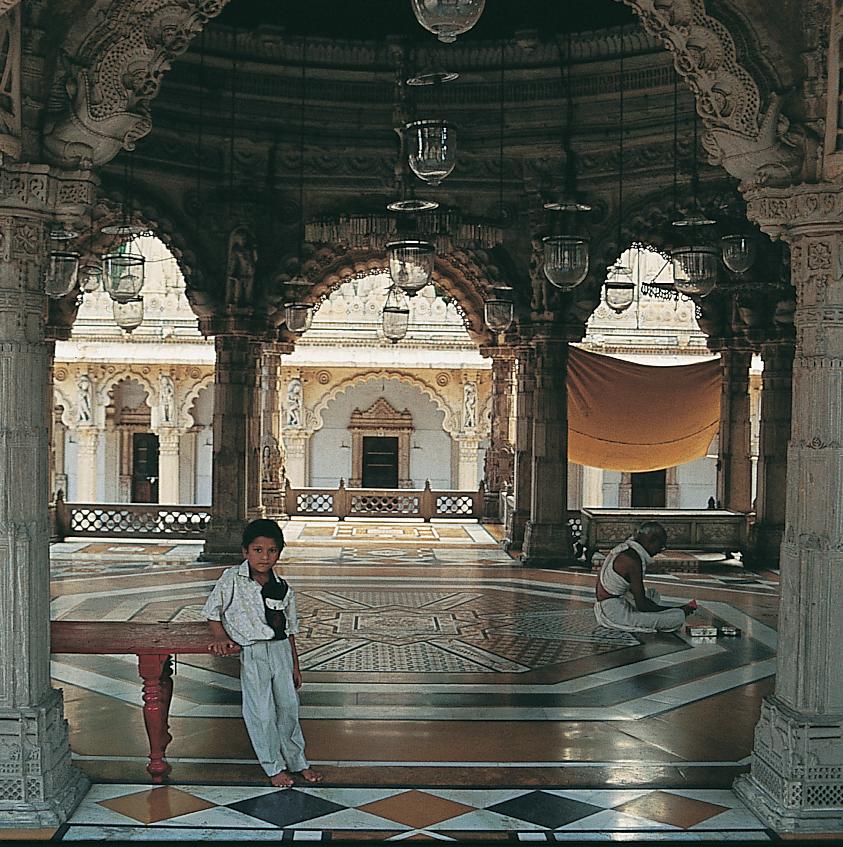

K INESTHETICSIN H UTHEESING JAIN T EMPLE , A HMEDABAD , 19 TH C ENTURY

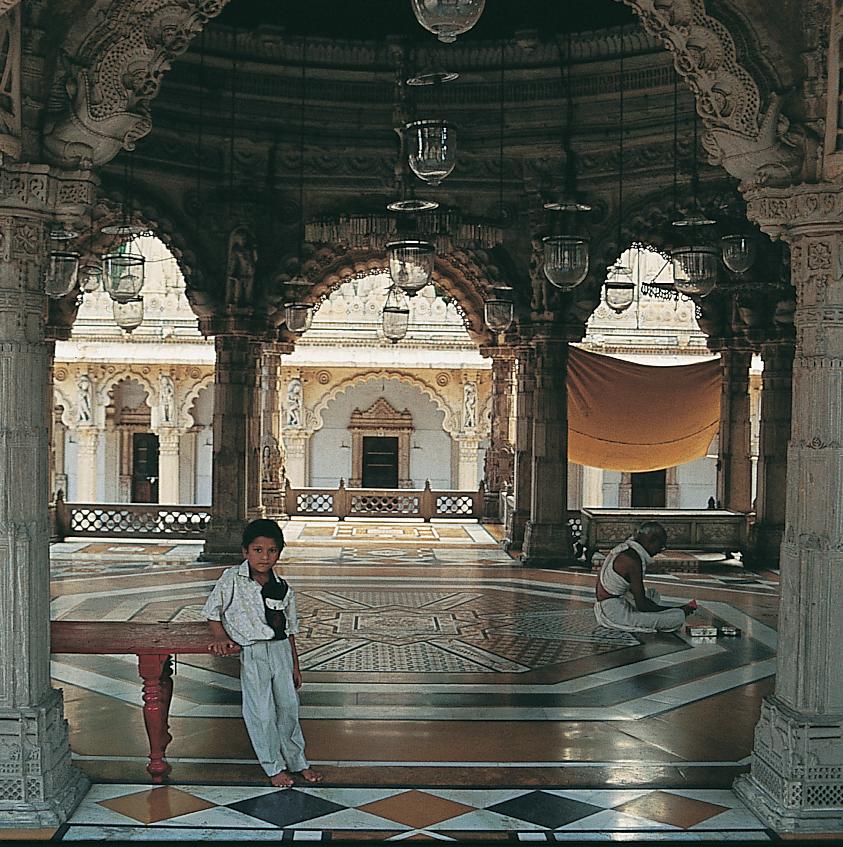

The Hutheesing Jain Temple in Ahmedabad creates a spatial sequence attaining a one-toone dialogue with the divine through shifting movement axes and a gradual morphing of spaces. The architectural resolution helps in such a conditioning through the spatial organization and juxtaposition of space-making elements. At Hutheesing Temple, the victory tower becomes the first visual reference and the focus from a distance. The next sequence of spaces begins from the extended, axially aligned entrance pavilion with ascending steps, a gateway and the first floor mass. The entrance gateway brings one en-face the main shrine, but this is where the circumambulatory takes over. A colonnade creates the peripheral ambulatory passage. Niches for idols of the tirthankaras, the 24 sanctified saints of Jainism whose presence throughout the journey start conditioning the mind, punctuate each intercolumnation. The more important of these have been specifically highlighted with bigger cella. These punctuations in the continuous path are also reflected in the enhanced flooring pattern, change in column rhythm and heightened shikhara size at cardinal points. These help in establishing pauses and cross-references to the main shrine to which they align. After circumambulation, the journey further is axial, where the ascending steps, rising shikhara profiles, decreasing intensity of light aided by religious sculptures help create a gradual sense of withdrawal from the corporeal world. The passage here also passes through the three stage filters of the sabha-mandapa, goodha-mandapa and the garbhagriha. The Hutheesing Temple, thus, is yet another glorious example of movement guiding perception and exalting the physical journey into a personal intuitive experience.

24

1: Circumambulatory at Hutheesing Jain Temple for conditioning of mind and gradually orienting towards the cella.

1

2: The victory tower assumes the visual identity as the landmark from a distance.

3: Contrasted against the blank peripheral wall, the intricately carved projecting portico defines the entrance, inviting movement.

4: The colonnade with tirthankara niches all along the circumambulatory initiates the visitor into the sacred realm.

5: Pauses along the movement path are punctuated through pronounced shikhara profiles, changing rhythm of columns as well as accentuated flooring patterns.

2: The victory tower assumes the visual identity as the landmark from a distance.

3: Contrasted against the blank peripheral wall, the intricately carved projecting portico defines the entrance, inviting movement.

4: The colonnade with tirthankara niches all along the circumambulatory initiates the visitor into the sacred realm.

5: Pauses along the movement path are punctuated through pronounced shikhara profiles, changing rhythm of columns as well as accentuated flooring patterns.

25 3 4 5 6 2 4 3 N 5 6

6: Ascending plinths, confinement and darkness gradually transcend to the cosmic.

N ARRATIVESTHROUGHNOTIONS PERCEIVED REALITYVERSUS PHYSICAL REALITY

Beginning from overall spatial organization to symbolic representation, narratives are creatively fused into the schema of Indian architecture through a number of devices. Primary amongst these is the usage of optical illusions and visual imagery. As interpreted by the Canadian architect Ron Lane-Smith, the entire proportioning system of ancient Indian architecture has been founded on the principles of visual coordination and perception at the human eye level. Perception from this specific level gives rise to unusual visual frames and compositions, imperceptible otherwise, created by perspectival alignments. The early cave temples creatively derive proportions and pauses putting into effect the principles of visual perception at the human eye level and using the visual axis at different points to bring out or hide selectively as one moves through. Such an exploration of space also discovers the juxtaposition of architectural elements to highlight prioritised visual compositions, creating optical illusions, revealing newer dimensions and connecting otherwise apparently unrelated and visually separated elements to act as significant foci, thus making the entire journey eventful.

This phenomenon of juxtaposition of visual frames is well demonstrated in the cave temples of Ellora. For example, in Cave 15, the door jamb into the court pavilion has niches near the top. Across, around 20 metres away, on the community quarter side at the upper level at each end, beside an apparent balcony projection are two angularly placed figures of

Caves from Ellora and Aurangabad illustrate how visual alignments become the actual proportioning tool.

1: Cave 2, Aurangabad.

2: Great Shiva Temple, Elephanta.

3: Sculpture on wall at Ellora Cave 15 visually coincides with the jamb niche 20 metres apart appearing as a bracket.

4: Key plan of the cave at Ellora indicating the view positions.

5, 6, 7 and 8: Visual frames which continually play with the scales and senses as one progresses along the edifice at Ellora.

26

1 2 3 4 5 678 5 6 7 8

Photo courtesy: Dilip Karpoor

superhuman entities. When one is just about to exit the mandapa, pavilion, the two gigantic figures across just fit into the niches. The juxtaposition makes them appear conjoined, providing architectural continuity across the intervening vista and giving a combined impression with the column bracket at the doorway. This creates a new imagery with a composite visual frame, giving added significance to the ensemble. The niche in the column capital exactly coincides with an inclined female figure on the wall across to give a combined expression with the column bracket at the doorway. These vignette compositions are used at times for visual scaling effects as well. As seen in the caves of Ellora, the sequential frames transform the vertical scales to horizontal expanses. In the first frame, from a distance, the overall scheme is perceived, not in totality but with concealment of portions of it. Here the scales are relative and do not refer to the human being. The next frame, perceived on approachingthe building along the axis, is of vertical proportions revealing only the height of the structure–a part of the whole. The frame seen from the centre of the constricted entry begins to expand horizontally and on entering the court, exposes the entire scheme, a horizontal expanse totally dwarfing the height of the structure.

These principles are effectively applied to landscape elements also. One such profoundly successful application is in the placement of the water body for vaju–ablution in mosques. The water of the tank reflects the crown of the dome, but its image in totality is glimpsed only at the point of squatting down for the ritual washing. This is a subtle narrative yet a profound event and experience in itself to lead, remind and reconnect the subject to the eventual goal.

9: Ablution pond reflecting the gateway and crown of Jami Mosque, Ahmedabad, once again reminding and reinforcing belief in the eventual goal.

27 9

N ARRATIVESTHROUGHNOTIONS S EMIOTICS

In a country enriched by tradition and folklore, almost every aspect of Indian life has a special significance, which is translated into symbolic expressions. Semiotics is, thus, yet another means of communication that, given the plethoraof associated values, conjures notions. Metaphors, signs and symbols are visual clues creating allegories, allusions and associations. These create notional realities absolving and overwhelming the obligation of the physical construct–the material reality. Mind wins over matter. For example, an abandoned wall or a tree trunk ceases to be perceived only as a three-dimensional object but assumes new meaning as a holy shrine owing to conjured associations. No longer identified as a tree or a wall, it gets primarily defined as a shrine through overlaid symbols and their implicit communication. The associations and values thus evoked by them convert the hitherto mundane objects to meaningful icons.

1: The sprouting branch of the tulsi (basil) and the swastik motif render the wall as a shrine.

2: A banyan tree is considered sacred and revered as a holy place due to its location near a shrine and the association to its implanter.

3: The hollow of a tree trunk is transformed into a shrine with religious motifs, the ritually lit diya, lamp, within the multi-point arched doorway.

4: Sanctity of the idols reverberates in the reverence of the tree.

28 1 2 3 4

5th Reprint

ARCHITECTURE Concepts of Space in

Traditional Indian Architecture

Yatin Pandya and Vastu-Shilpa Foundation for Studies & Research in Environmental Design

148 pages, 294 colour photographs, 169 b&w drawings

9 x 9” (229 x 229 mm), pb

ISBN: 978-81-89995-75-1

₹1395 | $35 | £25

2023 • World Rights

Yatin Pandya is an author, activist, academician, researcher as well as practising architect with his firm FOOTPRINTS

E.A.R.T.H. A graduate of CEPT University, Ahmedabad, with M.Arch. from McGill University, Canada, he was involved with architectural research as associate director of Vastu-Shilpa Foundation. Pandya has been involved with city planning, urban design, mass housing, architecture, interior design, and product design as well as conservation projects. He has been visiting faculty at National Institute of Design and CEPT University and guest lecturer/critic to various universities in India and abroad. Pandya is the author of several books on architecture, published internationally, and has written extensively for national and international journals. He has won many national and international awards for architectural design, research as well as dissemination, including the Indian Institute of Architects Award 2014 for Excellence in Architecture in the Research category for his book Elements of Spacemaking.

Pandya also won the ARCHIDESIGN Award for Excellence in Architecture for Best Written Work in 2006 for Concepts of Space in Traditional Indian Architecture. He won the Indian Institute of Architects Award for Excellence in Architecture in Research category in 2012 for this book.

OTHER TITLES OF INTEREST

tHE ARCHItECtuRE of HASMUKH C. PATEL

Selected Projects 1963–2003

Catherine Desai and Bimal Patel

DESIGNING FOR MODERN INDIA INI Design Studio

lEARNING fRom INDIA SERIES LEARNING FROM DELHI

Practising Architecture in Urban India

Pelle Poiesz, Gert Jan Scholte and Sanne Vanderkaaij Gandhi

A WALKING TOUR: AHMEDABAD

Sketches of the City’s Architectural Treasures

Matthijis van Oostrum and Gregory Bracken

MAPIN PUBLISHING

www.mapinpub.com

“

Pandya guides the reader on a walk through these monuments... revealing the worlds within worlds—giving the journey a kinetic dimension that moves the reader forward, inviting him to discover more.

” —Marg

Printed in India

“A monumental effort.”

The Indian Express

“The strength of the book is its sumptuous illustrations. The diagrams that accompany the illustrations help convey the analysis.”

The Hindu

“

Concepts of Space provides an interesting perspective from which to view familiar monuments. Pandya guides the reader on a walk through these monuments, ...revealing the worlds within worlds—giving the journey a kinetic dimension that moves the reader forward, inviting him to discover more.”

—Marg

—Marg

Excellence in Architecture 2012

Excellence in Architecture 2012

Winner of

2: The victory tower assumes the visual identity as the landmark from a distance.

3: Contrasted against the blank peripheral wall, the intricately carved projecting portico defines the entrance, inviting movement.

4: The colonnade with tirthankara niches all along the circumambulatory initiates the visitor into the sacred realm.

5: Pauses along the movement path are punctuated through pronounced shikhara profiles, changing rhythm of columns as well as accentuated flooring patterns.

2: The victory tower assumes the visual identity as the landmark from a distance.

3: Contrasted against the blank peripheral wall, the intricately carved projecting portico defines the entrance, inviting movement.

4: The colonnade with tirthankara niches all along the circumambulatory initiates the visitor into the sacred realm.

5: Pauses along the movement path are punctuated through pronounced shikhara profiles, changing rhythm of columns as well as accentuated flooring patterns.

—Marg

—Marg

Excellence in Architecture 2012

Excellence in Architecture 2012