Vol. 07 No.01 I Spring 2022

The Journal of Film & Visual Narration

CONTENTS

Vol.07, No.01 | Spring 2022

OVERVIEW

ii About MSJ

iii Letter from the Editor Greg Chan

iv Contributors

ARTICLES

01 Naderi’s The Runner: Trauma of Modernity and Desire for the Machine Amir Barati

FEATURETTES

14 The End of Everything: Millennium Anxiety in Gregg Araki's Nowhere Henrique Brazão

18 A Close Look at the Perception of Power in Carol

Alexandria Jennings

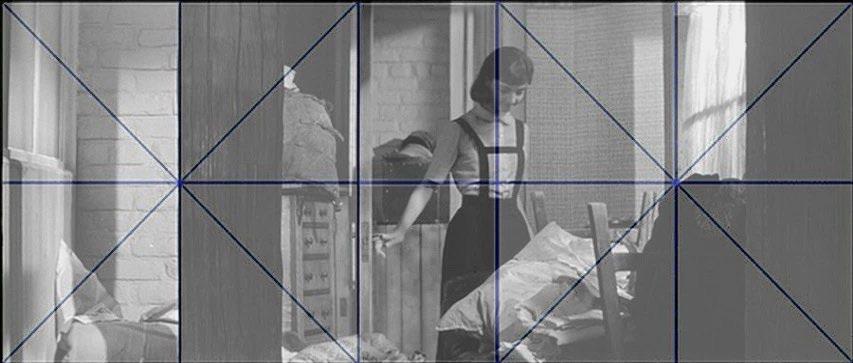

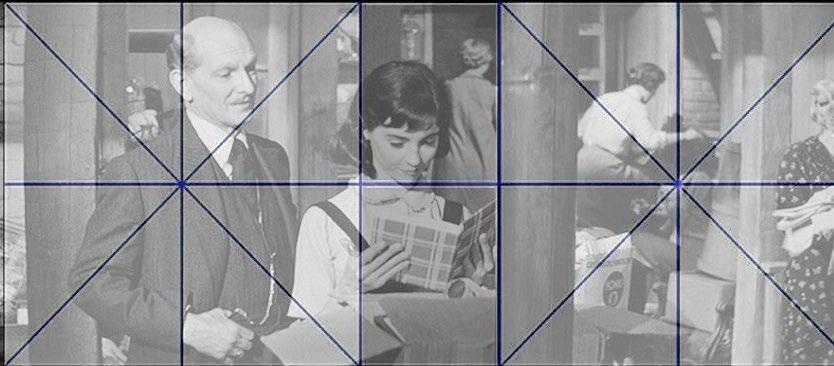

22 The Precise Composition of The Diary of Anne Frank

Marshall Deutelbaum

25 Cinematic Isolation and Entrapment in The Lobster Mazyar Mahan

INTERVIEWS

29 An Interview with Director Cathy Brady Paul Risker

UNDERGRADUATE SCHOLARSHIP

34 Creating Space for Belongingness in Midsommar Matthew Scipione

BOOK REVIEWS

39 Breaking Bad and Cinematic Television Paul Tyndall

ANNOUNCEMENTS

42 Open Call for Papers

43 About the Journal

MISE - EN - SCÈNE i

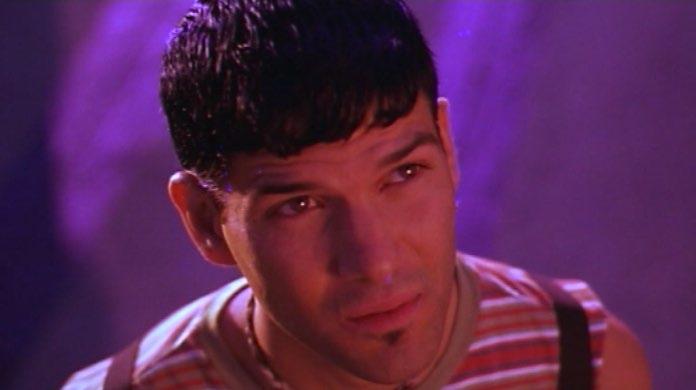

Gregg Araki's Nowhere. Fine Line Features, 1997.

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF

Greg Chan, Kwantlen Polytechnic University (KPU), Canada

ADVISORY BOARD

Kelly Ann Doyle, KPU, Canada

Richard L. Edwards, Ball State University, USA

Allyson Nadia Field, University of Chicago, USA

David A. Gerstner, City University of New York, USA

Michael Howarth, Missouri Southern State University, USA

Andrew Klevan, University of Oxford, United Kingdom

Gary McCarron, Simon Fraser University, Canada

Michael C.K. Ma, KPU, Canada

Janice Morris, KPU, Canada

Miguel Mota, UBC, Canada

Paul Risker, University of Wolverhampton, United Kingdom

Asma Sayed, KPU, Canada

Poonam Trivedi, University of Delhi, India

Paul Tyndall, KPU, Canada

REVIEWERS

Michael Howarth, Missouri Southern State University, USA

Michael Johnston, Kutztown University of Pennsylvania

Dan Lett, KPU, Canada

Mazyar Mahan, Chapman University, USA

Gary McCarron, Simon Fraser University, Canada

Christina Parker-Flynn, Florida State University

Novia Shih-Shan Chen, KPU, Canada

COPYEDITORS

Heather Cyr, KPU, Canada

Janice Morris, KPU, Canada

Robert Pasquini, KPU, Canada

LAYOUT EDITOR

Patrick Tambogon, Wilson School of Design at KPU, Canada

WEBMASTER

Janik Andreas, UBC, Canada

OJS CONSULTANT

Karen Meijer-Kline, KPU, Canada

The views and opinions of all signed texts, including editorials and regular columns, are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent or reflect those of the editors, the editorial board or the advisory board.

Mise-en-scène: The Journal of Film & Visual Narration is published by Kwantlen Polytechnic University, Canada

WEBSITE

journals.kpu.ca/index.php/msq/index

FRONT COVER IMAGE

Courtesy of Alamy

BACK COVER IMAGE

Courtesy of Jake Hills on Unsplash

SPONSORS

Faculty of Arts, KPU KDocsFF

KPU Library

English Department, KPU

CONTACT

MSJ@kpu.ca

SOCIAL MEDIA

@MESjournal facebook.com/MESjournal UCPIPK-f8hyWg8QsfgRZ9cKQ

ISSN: 2369-5056 (online) ISSN: 2560-7065 (print)

Vol.07 No.01 | Spring 2022 ii About MSJ

Dear Reader:

Welcome to the Pride Edition of MSJ: a special collection reflecting on LGBTQIA2S+ resistance, resilience, and representation.

The dossier before you puts the spotlight on LGBTQIA2S+ Otherness and queer spaces in films ranging from Todd Haynes’s Carol (2015) and Ari Aster’s Midsommar (2015) to Yorgos Lanthimos’s The Lobster (2015) and Gregg Araki’s Nowhere (1997). Coinciding with annual Pride celebrations—June being Pride Month in Canada and elsewhere internationally—Issue 7.1 invites you to invest in LGBTQIA2S+ and queer adjacent narratives captured in the frame. As with all of our journal’s themes, Pride emerged organically to become the issue’s unifying voiceover.

Another unifying element is Issue 7.1’s focus on the mise-en-scène featurette. Typically, our issues are anchored by feature-length articles. However, our Pride edition specializes in concentrated film analyses at the level of the frame. I invite you to immerse yourself in our collection of five featurettes that break down the artistry of a scene through individual frames. One of those featurettes is by Matthew Sciopione, this edition’s undergraduate scholar. If you’re looking for a long-form analysis, we have you covered with Amir Barati’s article on Naderi’s The Runner.

On behalf of everyone here at MSJ, I am proud to announce that KPU’s Faculty of Arts has joined us as our Headlining Sponsor and KPU’s Department of English—the journal’s home base for the last seven years—has come aboard as our Premier Sponsor. Special thanks to Dr. Greg Millard, Pro Tem Dean of Arts, and Dr. Robert Dearle, English Department Chair, for their generous support. With their sponsorship, the MSJ team looks forward to sharing film studies scholarship with you for many years to come.

Finally, I would like to offer a sneak peek at our upcoming issue (7.2, Winter 2022), which will be a themed edition on horror guest edited by Michael Howarth from Missouri Southern State University. Dr. Howarth is a long-serving member of the MSJ advisory board and review team who specializes in filmic horror. His themed call for papers has resulted in an exciting collection of articles and reviews (film festival and book), along with a video essay and an interview with Dacre Stoker (great grandnephew of Bram Stoker). I am grateful to Dr. Howarth for stepping in as guest editor while I am on sabbatical.

With Pride,

Greg Chan Editor-in-Chief

MISE - EN - SCÈNE iii

LETTER FROM THE EDITOR

Amir Barati is an interdisciplinary scholar interested in American minority literature, neuro-psychoanalytic theory, and film studies. His research focuses on the representations of traumatic bodies in American diasporic literature and films. Amir is currently a graduate instructor and PhD candidate in English and Humanities at the University of Missouri in Kansas City. His former publications address diverse issues including processual subjectivity and plasticity, apocalyptic imaginations, and body politics in American and British fiction and films. Amir has been editing for Kansas City Voices, Tête-à-Tête (published by Louisiana State University), and UMKC’s Journal of Interdisciplinary Research.

HENRIQUE BRAZÃO

Born in 1993, Henrique Brazão is a Portuguese filmmaker, independent film scholar and activist based in Lisbon. With a BA in Screenwriting from Lisbon Film School (ESTC) and a Masters degree in Communication Sciences from Lisbon’s NOVA University, he has written and directed two short fiction films –Em Junho (2019) and Farol (2022) – both about gaining freedom through sensory experience. He is currently preparing an application for a PhD program, intending to produce solid written work about cinema at the turn of the millennium.

Vol.07 No.01 | Spring 2022 iv

AMIR BARATI

CONTRIBUTORS

Marshall Deutelbaum is Professor Emeritus in English at Purdue University. He is co-editor with Leland Poague of A Hitchcock Reader, 2nd ed. (Wiley-Blackwell, 2009). Professor Deutelbaum was on the staff of the Film Department of George Eastman House during the 1970s. Among his curatorial responsibilities was teaching courses in film history at the University of Rochester. From 1980 until his retirement in 2005 he taught courses in film history and theory in the English Department at Purdue University. His many publications include number on the films of Hong Sangsoo. This essay is a portion of his ongoing research into the visual logic of widescreen filmmaking. His most recent publication is “’Why Does It Look like This?’ A Visual Primer of Early CinemaScope Composition,” published online in Movie: A Journal of Film Criticism. It is available at https://warwick.ac.uk/fac/arts/scapvc/ film/movie/contents/whydoesitlooklikethis_v04.pdf

Alexandria Jennings is a recent graduate of Youngstown State University where she earned her Master of Arts in English. In the fall she will be attending The University of Pittsburgh as a doctoral student, focusing her work in the field of composition and rhetoric. Her master’s work was situated in the disciplines of discourse theory, film studies, queer theory, and early American literature. During her time in the program, she taught in the university’s composition program which led to the development of a case study aiming to investigate the common misconceptions about writing that first-year writers possess. Alexandria has also spent a great deal of time conducting research in the realm of queer theory which she attributes to helping forge her scholarship in queer film. Her scholarship on lesbian power dynamics and autonomy on screen in the film, Carol (2015) has prompted her to work on other film-based projects concerning the intersection of imperialism and satire in both visual and written texts. This is her first academic publication.

MISE - EN - SCÈNE v Contributors

MARSHALL DEUTELBAUM

ALEXANDRIA JENNINGS

Mazyar Mahan is a Teaching Associate and PhD student in Visual and Performing Arts at the University of Texas at Dallas, where he teaches Transnational Film and Video. His research interests include global and transnational cinemas, cultural studies, and contemporary Iranian cinema. Mazyar has presented his research at conferences such as the Society for Cinema and Media Studies (SCMS), the National and the Southwest PCA, and the University of Southern California Film Studies Conference. His scholarly work appeared in journals such as The Spectator

Paul Risker is an independent scholar, freelance film and literary critic, and interviewer. Outside of editing MSJ’s interview and film festival sections, he mainly contributes to PopMatters, although his criticism and interviews have been published by both academic and non-academic publications that include Cineaste, Film International, The Quarterly Review of Film and Video, and Little White Lies. He remains steadfast in his belief of the need to counter contemporary cultures emphasis on the momentary, by writing for posterity, adding to an ongoing discussion that is essentially us belonging to something that is bigger than ourselves.

Vol.07 No.01 | Spring 2022 vi Contributors

MAZYAR MAHAN

PAUL RISKER

MATTHEW SCIPIONE

Matthew Scipione is a writer and director. He earned his Bachelor of Arts at Curry College, where he majored in Communication with a concentration in Film Studies. His essay “Transnational Filmmaking: The Intersubjective Gaze in Desierto” was published in Film Matters earlier this year. Furthermore, his short film King of the Imaginations premiered at IFFBoston this spring. King of the Imaginations is currently being submitted to festivals, as he develops his forthcoming project.

Paul Tyndall completed a PhD in English at Dalhousie University in Halifax, Nova Scotia. He currently teaches literature and film in the Department of English at Kwantlen Polytechnic University in Surrey, B.C. His main teaching and research interests include contemporary American literature and film and Shakespeare on film and television. He is currently engaged in a book-length study on representations of Shakespeare's history plays on film and television. In addition to his teaching and research, he serves on the advisory board of Mise-en-scène: The Journal of Film & Visual Narration.

MISE - EN - SCÈNE vii Contributors

PAUL TYNDALL

Vol.07 No.01 | Spring 2022 viii

Naderi’s The Runner

Trauma of Modernity and Desire for the Machine

BY AMIR BARATI University of Missouri

ABSTRACT

Amir Naderi’s The Runner (1984) heralds a golden age in Iranian cinema. The film portrays the extensive historical rupture caused by the violent force of an imported modernity introduced to the Iranian traditional society, and how desiring bodies in a developing country are breached in competition with the western machine. A unique product of Iranian cinema, the film depicts a nation’s optimistic quest for the synchronization of parallax ways of being. In other words, it echoes the Iranian endeavor to emerge from local convention and accept the extrinsic intruder. Simultaneously, while showcasing the first modern Iranian city, The Runner displays the historical turmoil that bloody wars produced for the native population, generating an ambivalent yet precise image of a war-torn society transitioning toward modernity.

INTRODUCTION

Amir Naderi’s The Runner (1984) heralded a golden age in Iranian cinema. The film was among the first Iranian productions to win an international award after the 1979 Islamic Revolution.1 Yet The Runner never received adequate critical attention for its historical and psychosocial significance. Most scholarship on the film either focuses on its autobiographical implications, which reference the director’s personal life and his childhood, or stresses the ideological shadow of the Islamic Revolution. These readings have distracted from a genuine analysis of The Runner as a philosophical contemplation on a society on the cusp of a critical era, in the midst of a huge modernization project, and facing traumatic upheavals, political revolution, and constant bombardment by one of the most powerful militaries of its time: Saddam Hussein’s Ba’athist army of Iraq. The movie should be read as a meditation on the material impacts of historical events and social conditions on human bodies in a Middle Eastern context.

The Runner reveals the story of a teenager named Amiro (Majid Niroumand), who lives in a slum in a hot and humid Iranian southern port city—likely Ābādā n. Talented, resolute, peculiar, and independent, Amiro—an orphan—is highly competitive and ready to fight for his rights. He waves at ships leaving the harbour and runs to visit his favourite airplanes, collecting their images. He makes a living through various jobs including garbage collecting, shoe-shining, and selling ice water. In a sense, the film is a portrayal of Amiro’s love for huge machines and his efforts to win the demanding games he plays with other children. Initially, he loses these games, but after relentless determination, he wins the last one. Through all of this, he also manages to go to school and learn the Persian alphabet.

Hamid Nafisi, a prominent critic of Iranian transnational cinema, views The Runner on the backdrop of the messianic ideologies of the Islamic Revolution (213). He considers the

1 The Runner won the Golden Montgolfiere in Nantes Three Continents Festival in 1985.

MISE - EN - SCÈNE 01

ARTICLE

Naderi’s The Runner : Trauma of Modernity and Desire for the Machine

film a “proto-exilic movie” and one of “Iranian cinema’s most graphic inscriptions of the desire to escape the homeland for foreign lands” (505). He also assumes the film foreshadows Naderi’s immigration from Iran years after its production. A host of other established Iranian critics share this view, observing The Runner as an expression of the desire to depart from a troubled country. On the other hand, S. Zeydabadi-Nejad notes how the film coincides with “the values of the Islamic regime for being about the lives of mostada’fin (the downtrodden)” and the working class who formed the Islamic Revolution (380). Since the movie was released only five years after the 1979 Islamic revolution and was funded by a public educational institution, a fair number of other critics have overlooked the film’s broader historical appeal and have considered it to be a direct political response to the Islamic Revolution.

Kamran Rastegar is one of the rare scholars who briefly comments on the film’s historical references, pointing out traces of the traumatic Iran-Iraq war. Rastegar writes, “The Runner represents a sublimated response to the effects of the war” (146). He highlights the protagonist’s quest for a new subjectivity as a tale of becoming. Far from the typical politically motivated

stratified between affluent foreigners and local children who live on the streets and make a living collecting recyclables? Why is the land on fire while children run after ice? Responses to these questions require a thorough exploration of the social condition that produced this lifestyle and the director’s worldview. I aim to explore the traumatic history of the society illustrated by Naderi in The Runner and examine the intellectual and cinematic choices the director and his crew made in the production of the film. Believing that “the truth of narrative isn’t in the fact-checking, but in the trauma it circles” (Richardson 505), I argue that Naderi’s film represents the extensive historical rupture as caused by the violent force of modernity imported into traditional Iranian society and how that society’s desiring bodies are breached while competing with the Western machine. Modern machinery and an accompanying contemporary Western lifestyle were introduced to traditional Iranian society mainly through the force of the military or via interactions with semi-colonial industries.2 The desirable power of the modern machine and the violent force of its semi-colonial introduction created a traumatic ambivalence that I will try to articulate in this paper.

Modern machinery and an accompanying contemporary Western lifestyle were introduced to traditional Iranian society mainly through the force of the military or via interactions with semi-colonial industries.

characterizations of the era, the film propagates a progressive and processual subjectivity that is unique in Iranian cinema of the time (Barati and Eslamieh 121). This rare critical standpoint is echoed in Alla Gadassik’s views. Gaddassik argues that The Runner is preoccupied with a kind of cultural displacement and fragmentation which “cannot and will not be remedied through migration elsewhere” (482). For Gaddassik, the fact that Amiro is always living on the margins is of supreme importance to the overall philosophy of the text (477). Nevertheless, the film offers a much more sophisticated perception of the subject’s position within the temporal displacement and historical rupture experienced by Southern Iranian communities.

Moving beyond an analysis of The Runner as a production of its auteur director who comments on it from an autobiographical standpoint, many fundamental questions emerge for the viewer: why is Amiro always running? How should we interpret his fetishistic affection for airplanes and ships? Why is he parentless and living alone? What is the reason behind the heavy presence of machinery? Why is this colonized society

This approach is informed by Jacques Lacan’s argument in Seminar XI (1973) where he discusses the human encounter with modernity and how the automaton fashioned a traumatized modern mentality. According to Lacan, modernity’s production of massive machinery introduced a new aspect of “the real” to humanity. For him, the “real is that which always lies behind the automaton” (55). The real as an encounter causes an unassimilable rupture in the symbolic register of subjects. Based on this viewpoint, the introduction of modern machinery to human life created a new paradigm, causing a historical rupture in the human’s consciousness and signaling a new era that radically diverged from past ones. Therefore, modern subjects—whose previous stories about themselves do not work anymore—use their bodies to recreate and re-narrate themselves in a bid to work through this historical trauma and fill the psychosocial gaps produced by the rupture.

In this respect, The Runner is a materialist contemplation on the emergence of modernity and modern consciousness as well as the ruptures it produced in Iranian society. The film

2 I avoid using the term colonial or postcolonial because Iran was never really colonized in the true sense of the word, as compared to the way India was colonized by Britain or parts of Africa or America were colonized by Europeans. The presence of foreign forces in Iranian contemporary history has always mainly been limited to bordering regions. Thus, the term semi-colonial refers to the temporary presence of foreign military and tradesmen with colonial intentions and their conflicts with the natives in the regions.

Vol.07 No.01 | Spring 2022 02

reveals the historic epiphany offered to Iranians that coaxed them to master the discourse of the machine as a prerequisite to dealing with the imported automaton. In terms of the discourse of the machine, I aim to express the awareness of the social, cultural, and historical contexts that lead to the production and mass use of modern machinery in the West. I claim the literacy that grew from the European enlightenment in the 17th and 18th centuries and stretched to the 19th and 20th centuries was critical to the creation of the modern machinery; this long cultural background of technological advancement created an invisible internal readiness for the birth of the automaton. This knowledge of the historical necessity, social functionality, material value, and cultural prospect of the modern machinery that was available to the Western society is what I call the discourse of the machine . This perspective considers The Runner as a symbolic text projecting the larger existential dilemmas and contradictions of the machine age due to its fetishistic desires.

The film imagines the new Iranian subject emerging from its traditional views, confronting this imported phenom -

machinery and the amenities of modern life to the region, many of which are represented in The Runner. In 1910, 2,500 Iranian workers were employed by the British oil company, with the number jumping to 17,000 people in 1918. The new settlement housed a diverse population of domestic and international settlers who moved to the region to work in the oil and trade sectors. Ābādān—The Runner’s supposed setting—was the first major Iranian city born out of the modern oil industry. By the 1930s, the British constructed the largest oil refinery plant in Ābādān (Amanat 565).

Despite fruitful interactions and cooperation between the Anglo-Persian Oil Company and Iranian tribal leaders, and the relative security associated with the modern economic development of the southern port regions of Khuzestan province, many conflicts occurred. The invasion of Iran in both World War I (the Persian campaign of 1914-18) and World War II (the Anglo-Soviet invasion of 1941) as well as the droughts, diseases, and devastations they brought to Iran created a sense of humiliation, fear, and animosity towards foreign forces in the collective Iranian mind (Motaqedi et al. 128). In World

This cultural exchange with the Western Other and its contemporary machinery produced a historical fetishistic fascination with technology and power, which was contrasted by a fearfulness and frustration with the destructive powers of modernity—including the modern military.

enon, and living with its associated traumas. Because it was produced during Iran-Iraq war, The Runner attempts to move away from the latest historical trauma the war produced for the native population. While limiting its scope to the south of Iran, the imagery generated by the film symbolizes modern Iranian society in a time of transition and highly affected by its media and technologies.

THE TRAUMA OF MODERNITY IN SOUTHERN IRAN

Before engaging with the film, a historical background on the southern provinces of Iran is necessary. Iran’s only access to international waters is through the southern Persian Gulf and Sea of Makran stretching from Ābādān and Mahshahr to Bandar Abbas and Chabahar. Historically, the port cities and islands in this region have been maritime hubs for Iranians to interact and connect with the Western world. The area’s semi-colonial impression came from Portuguese, Ottoman, Russian, Dutch, and British imperial military presences in the region as well as international seafarers and traders.

But when the British excavated the first Middle Eastern oil wells in the Iranian province of Khuzestan (specifically the city of Masjid Suleyman) in 1908, the event revolutionized the southern port cities. The oil-export industry introduced huge

War I, the popular outrage and frustration from foreign intervention stirred popular movements and militias in tribal and ethnic populations. Among all popular regional uprisings, the southern tribal revolts of Boyer-Ahmad, Tangestan, and Larestan against British occupiers during World War I marked pivotal moments in Iranian cultural memory. The remembrances and narratives of this trauma remained alive for decades after. For example, the Iranian TV series Braves of Tangestan (Homayoun Shahnavaz, 1974) recalls the trauma of the British presence in the southern trade port city of Bushehr. The series recounts the heroic uprising of the southern historic figure Reis Ali Delvari against the British occupiers in 1915.

Naderi’s earlier film Tangsir (1973) recalls the same incident in which the film’s hero, Zar Mohammad (Behrooz Vossoughi), is a solider in Delvari’s battalion. In Tangsir , Naderi represents the revolutionary, nationalistic, and anti-colonial sentiments of the Iranian cultural consciousness. Eleven years after the production of Tangsir , Naderi moved beyond binary politics as demanded by the opposition between the oppressed and the oppressor. In The Runner , the director shares his contemplations on Iran’s fundamental ambivalence toward modernization.

Iranians in the region observed the oil industry, urbanization, and the relative security around the oil plant with

MISE - EN - SCÈNE 03 Amir Barati

Amiro becomes the symbol of a nation new to modernization that wishes for large-scale and sophisticated advancement but has yet to see it materialize.

In Ābādān, the British neighbourhood was a source of fascination for the local population who lived in poor conditions yet worked hard for low wages. This social stratification added to the incongruities in the collective memory of the southern people that compelled them to view the rich occupiers either as colonial forces exploiting their country’s natural resources or as flag-bearers of modern machinery and technological advancement. The economic disparity in Ābādān remained an acerbic part of the city’s fabric. In this respect, the “development of the oil industry thus introduced in Ābādān a sociocultural stratification unparalleled in other Iranian cities” (De Planhol), a result of the introduction of modern industrialism to the local population by Westerners.

For the people of this southern region, Western forces played dual roles as bearers of machinery and inflictors of colonial trauma. As the positive power of modern machinery was observed, these individuals also witnessed how technology could inflict miseries in their new careers. The same contradictory feeling was projected on machinery and towards the West and all modernization projects in general. The working class in Iran’s southern regions could admire the power of modern machinery and technological advancements. They could observe the benefits of the oil industry. But the same technology was deployed to oppress them, thus creating a fetishistic aura of equal parts fascination and antagonism directed towards the automaton that still looms large in Iranian society.

The Runner portrays Iranian society right after the 60s and 70s when Iran experienced radical modernization. The Iranian Pahlavi dynasty (1925-1975) was the forceful proponent of extensive Western modernization in cooperation with multinational companies. This fast-developing modernization project left some communities dispossessed or ignored. Naderi’s film is about how this community views their changed society and how they should ideally operate within it. The didactic aspect of the film for young generations lies in the message for the dispossessed to struggle to seek knowledge as the source of power. This idealist message in an existential film also contributes to the ruptures in a society where desires should be kept dear, irrespective of the challenges.

fascination and admiration. However, the occupations and military confrontations of the two World Wars had left them with much devastation and trauma (Fig. 1).

This cultural exchange with the Western Other and its contemporary machinery produced a historical fetishistic fascination with technology and power, which was contrasted by a fearfulness and frustration with the destructive powers of modernity—including the modern military (Fig. 2).

Amiro becomes the symbol of a nation new to modernization that wishes for large-scale and sophisticated advancement but has yet to see it materialize. Despite his desires, Amiro is doomed to dwell in a broken vessel and play within the wreckages of old yachts. This unfair competition between the human body and the Other’s machine is traumatizing for developing communities who face similar competition and its consequences. But Naderi favours the pathetic struggles that overcome any challenges.

THE JAMMED MACHINE IN A MODERN IRAN

Without question, the machine is an integral part of The Runner. Trains, ships, planes, trucks, and bicycles are omnipresent in the film, yet machines work at two symbolic levels in Iran’s cultural

Vol.07 No.01 | Spring 2022 04

The Runner : Trauma of Modernity and Desire for the Machine

Naderi’s

Fig. 1 | Amiro collecting garbage in Naderi’s The Runner, 00:05:05. Center for the Intellectual Development of Children and Young Adults, 1984.

Fig. 2 | Amiro polishing foreigners’ shoes in Naderi’s The Runner, 00:57:19. Center for the Intellectual Development of Children and Young Adults, 1984.

consciousness. There is the side of the Other: a world of sophisticated machinery, beautiful and massive cruise ships, sturdy airplanes, fast trains, and fanciful magazines (Fig. 3).

On the other hand, there is Amiro’s side: a world of jammed machines, wrecked ships, garbage caused by the machine age, slums on the edge of land laid to waste by heavy machinery, and empty bottles of alcohol. Even working bikes are borrowed. The contrast between these two worlds best represents Naderi’s intellectual observations on industrialization and its effects in the Middle East.

On first viewing, the two worlds Naderi depicts seem modernist and Chaplinian. Naderi considered Charlie Chaplin to be “among his earliest ‘teachers’” (Gadassik 475). In his portrayal of these contrasting worlds in the machine age, Naderi alludes to Chaplin’s films. For example, Amiro is presented as a Chaplinian little tramp. He is society’s underdog, living a vagrant’s life while trying to become successful. He is diligent and forever hopeful. He respects human value in a competitive working-class society. As in Chaplin’s Little Tramp (1936), Amiro is an outcast who strives to compete with others but always keeps his own dreams and desires within reach. Naderi even pays homage to Chaplin in the scene when Mousa (Musa Torkizadeh), Amiro’s closest friend, walks in a style similar to Chaplin in Little Tramp , provoking laughter from Amiro (Fig. 4).

The short scene validates the idea that Naderi desired to create his own Middle Eastern Modern Times . In Chaplin’s film, workers must catch up with the speed of machinery in factory lines. In The Runner, a children’s game utilizes the best of the participants’ mechanical capabilities to compete with one another to match the speed of a moving train (Fig. 5).

In this tussle between plastic bodies and iron machines, the victorious ones are those who internalize the discourse of the machine and embody the mechanisms of the machine age.3 The rest would be left out of the game. This perception is apparent in both Modern Times and The Runner with the small caveat that Chaplin’s representation of modernism sympathizes with the nonconformist (the little tramp who does not want to abide by the rules of the machine age) while Naderi’s naturalism (referring to the inevitability of technological advancement) welcomes the ruthless struggle. Other comedians like “Keaton and Lloyd master locomotives, motorcycles, tin lizzies, street cars, steamboats and even ocean liners” (Gunning 241). However, for Amiro mastery does not happen. In The Runner, the machine has intruded the games of children. In most games, children compete with machines more than with one another. Mechanical movement as a source of power is an integral part of the children’s games in the film. Repeatedly, children test their capacities by chasing trains and outrunning bicycles. These demanding challenges represent a more existentialist vision of the machine age than that of Chaplin in Modern Times.

3 For more information on the plasticity of the body, please refer to Catherine Malabou’s

MISE - EN - SCÈNE 05 Amir Barati

The New Wounded (2007).

Fig. 3 | Magazines on a newsstand Amiro regularly visits in Naderi’s The Runner, 01:03:04. Center for the Intellectual Development of Children and Young Adults, 1984.

Fig. 4 | Mousa imitating Chaplin’s “tramp” walk in Naderi’s The Runner, 01:01:24. Center for the Intellectual Development of Children and Young Adults, 1984.

Fig. 5 | Children chasing a running train in Naderi’s The Runner, 00:43:03. Center for the Intellectual Development of Children and Young Adults, 1984.

Naderi’s divergence from Chaplin is most evident in his representation of Amiro’s responses to the requirements of industrial city life. Unlike Chaplin, who was highly critical of modernity and blamed the machine age for the source of much misery in the industrial world, Naderi seems to have moved beyond this criticism to highlight the ways in which human beings master the discourse of the machine. In this respect, Naderi is mainly Lacanian rather than Chaplinian in that he directs his camera towards the human’s desire for the power produced by machinery and technological advancement. In Chaplin’s cinema, there exists only fascination with but no desire for the hustle and bustle of modern city life. For Chaplin, modernity was an endogenous development in Western society that the public was not ready for. Yet for Naderi, this modernity is borrowed and imported from the West—from the modern and advanced colonial Other—and therefore the imported machine causes its own fetishism as an object of desire. These two layers need further elaboration.

its destabilizing composition and absence of exposition, this sequence would convince viewers to consider Amiro as a castaway desperate for help (Fig. 6).

The dream-like atmosphere persists when Amiro is shown behind the fence looking at an aircraft (Fig. 7). Amiro’s joy represents his desire for machines as a way to fly away from the shores and borders of his present circumstances.

These sequences have urged many critics to interpret the film as an expression of Naderi’s longing to escape his restrictive space. But this scene is only the beginning of Amiro’s dramatic and intellectual journey.

The machine turns out to be a fetishized obsession in The Runner. Amiro loves machines. He visits his beloved airplane almost every day after work. He communicates with ships by shouting at them. He keeps pictures of airplanes in his home. While collecting recyclables among garbage piles, he sees a cruise ship passing and says, “How white! How beautiful!” (00:05:42). White is a desirable colour under the region’s scorching sun,

The fetishistic obsession with modern machinery can be located in the games and actions of the children in the film while they constantly walk among heavy machinery.

From the beginning of The Runner, Naderi formulates the idea of the desire for the machine. The film begins by showing a portrait of Amiro in loose-fitting underwear and breathing heavily while he stares into distance for 13 seconds. As birds sing in the background, he begins shouting and waving a piece of cloth in his hand. The establishing shot shows a barren lagoon and a mirage in the background. A large ship appears far away from the shore. Then, Amiro turns into a dream-like figure, running and shouting on the shore. With

and what he perceives as beauty in the advanced machinery. Amiro spends his free time sitting at the port watching the passing ships. He buys a broken lamp to illuminate his traumatic world. Electricity and lamps are technologies that Amiro loves to own.

Amiro even beckons the industrial noises. Gadassik provides an insightful perspective of sound in the film by noting that the most notable sounds come from machines: “In The Runner , most of the memorable sounds do not

Vol.07 No.01 | Spring 2022 06

The Runner : Trauma of Modernity and Desire for the Machine

Naderi’s

Fig. 6 | Amiro running and shouting on the shore in Naderi’s The Runner, 00:02:20. Center for the Intellectual Development of Children and Young Adults, 1984.

Fig. 7 | Amiro is happy when he finds images of airplanes in Naderi’s The Runner, 00:33:25. Center for the Intellectual Development of Children and Young Adults, 1984.

come from within the immediate location but drift in from the margins. Sounds of cars, trucks and trains surround the frame and plant the viewer into the city’s industrial zone much more firmly than the relatively sparse visuals” (485). Amiro craves the noises of engines and industries, demonstrating an obsession with the industrial machines and their extensions into human life.

The fetishistic obsession with modern machinery can be located in the games and actions of the children in the film while they constantly walk among heavy machinery. Amiro sees the power in modern machinery and yearns for it. This desire for the power of the machine is not for the destructive power or strength of mechanical power. This desire originates from the will to overcome the unjust daily struggle Amiro faces. In the machine, he perceives the power to transform his life into a more affluent, less hot (hence the prevalence of ice in the film), more docile, and in general, richer existence. Despite the intensity of his desire, Amiro is left within the jammed machine: a wrecked ship (Fig. 8).

Amiro lives a slumdweller’s life and the only difference he knows between his own misery and the pleasure of the Other is that he has access to the run-down machine while the Other drives the fast-moving operational machinery. Thus, automation occupies the diverging space between misery and pleasure for Amiro.

Moreover, because the machine is a Western product in this southern port, and all the industries are imported into the region, Naderi shows how this imported mechanization affects the human body in a society which is completely naïve about it. The discourse of the machine is completely alien to the young boys, yet they must live through its alien discourse. The power imbalance between the bearers of technology and the local population also leads to further suppression of the impoverished local population, though these bearers have the potential to bring about productive change. Amiro stands on this ambivalent

position—on the border between his unconscious desires and material condition—desiring media representations of modernity that promise peace, prosperity, and power, and all the while living through the purgatorial conditions that imported modernity has created for him.

Moreover, the film illustrates the naïve mindset of local children as they compete with the machine by using their own mechanized bodies. All the children’s competitions with machines are doomed to fail; thus, Amiro struggles to find a way out of this mentality. To navigate their situation, Amiro begins to test alternate ways to compete with modern machinery. His bike race with an airplane is the pivotal moment in which he begins to think outside the box. Using the bike, Amiro attempts to absorb the discourse of the machine by using a machine to compete with another one (Fig. 9).

To master this discourse, Amiro finds photos of airplanes in aviation magazines to educate himself about them. He signs up for school in an attempt to learn the language of the machine, using linguistic literacy as a first step in education instead of relying on the mere use of his body in an unfair competition. The movie parallels linguistic literacy as a first step that enables the practitioners to read and begin their apprenticeship with the discourse of the machine. His education helps him to read magazines and further learn the discourse of the Other instead of living through the imaginary world of desires displayed in flashy magazines, beautiful pictures, and powerful planes. For Amiro, learning the discourse of the Other is synonymous with apprenticing the discourse of the machine since the Other owns the machine. Amiro wishes to master this technological culture of advancement (which has resulted in the pleasure of the colonial forces) with the hope that he may enjoy similar power and dominance over his life and others.

With respect to modernity and the condition of humankind at this age, Lacan assumes that human subjectivity cannot be defined only through the formula of inner necessities, but

MISE - EN - SCÈNE 07 Amir Barati

Fig. 8 | The wrecked ship where Amiro lives in Naderi’s The Runner, 00:19:51. Center for the Intellectual Development of Children and Young Adults, 1984.

Fig. 9 | Amiro racing an airplane on a bike in Naderi’s The Runner, 01:05:04. Center for the Intellectual Development of Children and Young Adults, 1984.

that it should be defined based on the world from which it emerges. Material inventions including language, writing, machinery, clocks, and media form the subject, and extend their effects to the past because they become an inalienable part of human perception. Lacan opines that “the machine isn’t what a vain people think it is. It isn’t purely and simply the opposite of the living, the simulacrum of the living . . . . Pascal showed us that ‘the machine is tied to radically human functions’” (Seminar II 74). In a Lacanian manner, humanity’s functioning is contingent upon the way the machine age inscribes in us our subjective impulses. The same problem exists in The Runner. Having internalized the power of the machine as their object cause of desire, these machine-age children direct all their efforts to create the same mechanisms and automation in their bodies so as to match the speed, function, and power of the desired machine.

Among the machines, Amiro and the other children aim to recognize themselves and understand their own conditions. Thus, the only way to recognize themselves is either to define their subjectivity and agency in contrast to the desirable powerful machine or to recognize themselves through the social mirror of the Western seafarer whose lifestyle implies prosperity and happiness. As Lacan claims, “The subject is no one. It is decomposed, in pieces. And, it is jammed, sucked in by the image, the deceiving and unrealistic image, of the other, or equally by its own particular image. That is where it finds its unity” ( Seminar Book II 54). Accordingly, the children in the film

movements. The machine is liberating for Amiro because it has the power to move people beyond their bodily, geographical, and political boundaries and create new spaces free from corporeal limits.

Naderi’s film accords to theories of Lacan but addresses the specific historical trauma of Iran through a postcolonial lens that adds a significant dimension to Lacan’s discussion. The Runner shows how Western modernity colonizes an Iranian region’s socio-economic space and produces its own fetishistic desire in the Iranian collective mind. The power of the imported colonial machinery becomes the object cause of the desire for people who cannot access it but are governed by it. In this respect, the film’s “Ābādān is an exceptional laboratory for analyzing the contradictions caused by Iran’s economic development and industrialization” (De Planhol). Throughout the film, a sense of fragmentation and displacement causes viewers to constantly try to locate themselves in the scenes and composition, while most of these efforts will be doomed to fail. This sense of displacement is also a deliberate construct of the film to show the traumatic realities of modernity in traditional communities when, due to the special, historical, and symbolic ruptures that they encounter, people lose their position in the urban space. As Gadassik writes, “In addition to its uncertain temporal dimension, the film’s location is also fragmented and unclear” (477). This ambiguity—especially marked by the lack of establishing shots in the film—corresponds with the way the film portrays a fragmented space as a result of modernization and war.

Thus, with the help of Iranian director Bahram Beyzai as editor of The Runner, Naderi decided to cut the entire Iran-Iraq war out of his film … In light of such traumatic conditions, The Runner presents an allegorical representation of the psychosocial conditions that the war creates instead of showing the brutal realities of a war-torn society.

find their subjective presence through their encounters with machines, with the trains and airplanes as well as with the tradesmen and businessmen in the port. These encounters help them to perceive their identity and recognize themselves as supposed unified entities.

The magazine images that Amiro keeps might be ostentatious media, but, still, this American Dream-like object of desire helps him gather pieces of himself and project his unified identity in response to that imaginary world. In this way, Naderi best articulates the Lacanian assertions that “The symbolic world is the world of the machine” (Seminar Book II 47) and the “unconscious is the discourse of the other” (Seminar Book II 89). The Other for Amiro is the foreign tradesmen who disseminate the discourse of the machine. Therefore, Amiro’s unconscious desires are all captured in machines and their liberating

EFFACEMENT OF THE WAR MACHINES

Another aspect of modernity in The Runner which has been touched upon is the effect of the Iran-Iraq war (1980-88) on the film. Iranian war-time filmmakers have always attempted to capture the intensity of war scenes. However, the pain war creates is often absent because no representation can accurately capture that pain. Particularly, the severity of the experience of pain forbids any accurate and realistic representation to fully contain the suffering. Thus, with the help of Iranian director Bahram Beyzai as editor of The Runner, Naderi decided to cut the entire Iran-Iraq war out of his film.

Despite the presence of many indirect references, The Runner is deliberately stripped of all direct allusions to the war, which was ravaging most southern port cities of Iran at the time,

Vol.07 No.01 | Spring 2022 08

Naderi’s The Runner : Trauma of Modernity and Desire for the Machine

including Ābādān. The film was produced when many southern cities in Iran were ablaze from the Iran-Iraq war, but Naderi decided to hide the devastating events. Instead, he alluded to the consequences of wartime catastrophe. These images are remembrances of a history of modern damage inflicted upon the people of this region including displacements, poverty, the heavy presence of machinery, quarrels, fires of oil plants burning the skin, veterans with amputated legs, army jeeps on the roads, toxic air, and most important of all, the presence of children as traumatic subjects with specific social and psychological conditions. The use of fire and smoke along with the heat and heavy machinery is reminiscent of the war.

The Iraqi invasion of Iran in 1980 catalyzed one of bloodiest wars of the second half of the twentieth century due to its heavy use of imported modern artillery. This war—stretching to eight years of World War I-like trench warfare with approximately one million deaths on both sides—left the two countries with immense pain and devastation. The bombardments ravaged many southern cities of Iran, causing massive destruction and displacing scores in the Southern Khuzestan province where Amiro lives. In light of such traumatic conditions, The Runner presents an allegorical representation of the psychosocial conditions that the war creates instead of showing the brutal realities of a war-torn society. The film also contemplates how to deal with, confront, or escape this miserable space. The film also highlights the destructive force of the machine and the way this destructive part of the discourse is an integral aspect of it as well.

One of the key factors at play in minimizing the war was the film’s producing institute, the Center for the Intellectual Development of Children and Young Adults. The institute’s audience is predominantly children and young adults; consequently, there naturally comes the ethical responsibility to cut

out the violence of the war and aim for didacticism. Various references to the film can be directed toward the goals of omitting violence and being didactic, including the emphasis on the role of literacy in the development of children.4 For example, Amiro learns the Persian alphabet as a sign of his ultimate victory.

The effacement of the war could make the film unconsciously appealing to its young audience. In his Reflections on War and Death (1918), Sigmund Freud stresses that the human psyche has an “unmistakable tendency to put death aside, to eliminate it from life… to hush it up” (Reflections). Instead of portraying the brutalities of the war—an effort which always fails to fully represent the reality of death—Naderi decides to entirely eliminate direct war scenes and death from his film. All that remains from the war are its threats, ghosts, and traumatic aftermaths. It seems as if, for Naderi, the actual event does not exist due to its temporary nature, but the reality of war lives on through its aftermath and the ruptures it creates in the social fabric and memory of the people who survive it.

Here, a psychoanalytic conflict exists between the pleasure principle and the death drive: Amiro tries to seek pleasure in a traumatic society ruled by war and the forces of death. The harsh games played by The Runner’s children can also be analyzed in this sense. The boys, most of whom share Amiro’s living conditions, take part in dangerous games to rehearse and rediscover parts of themselves that have been lost to this traumatized society. The conflict over ice best reveals the nature of this competition as an existential battle of adhering to the objects of desire. As a game based on out-injuring the opponent, the defeated ones represent the dead, while the ones who desire the power of the machine can narrate the war as a victory for themselves. In such a situation, the desire for the power of the machine becomes an existential one driving the subject towards their survival (Fig. 10).

These children constantly attempt to resituate their existence amid a fragmented social fabric whose symbolic texture has been torn apart by repeated traumas. Overall, without overtly pointing out the true causes behind the problem, the concealment of war still constructs a narrative which reveals many consequences for war-time children. The film shows the misery tolerated by the protagonists in a more productive manner, calling the young audience to work through the despair and identify with the assiduousness and competitive aspirations of Amiro.

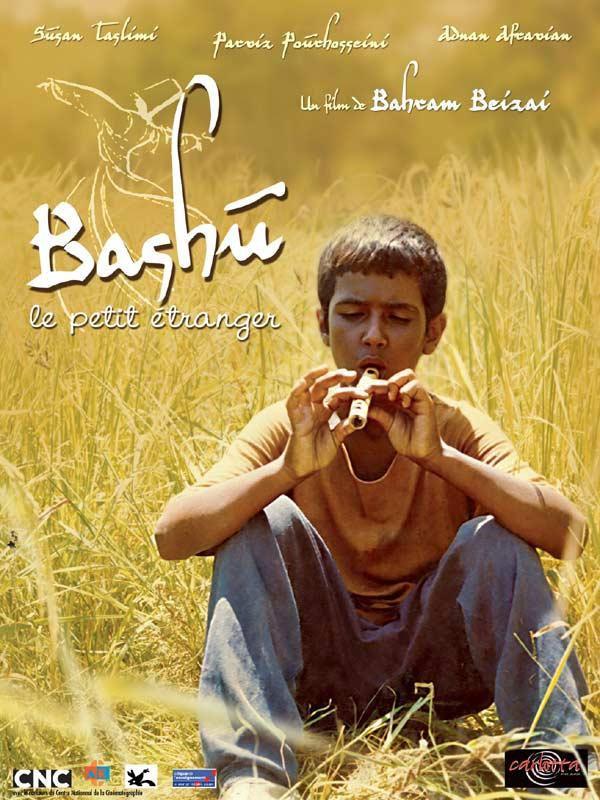

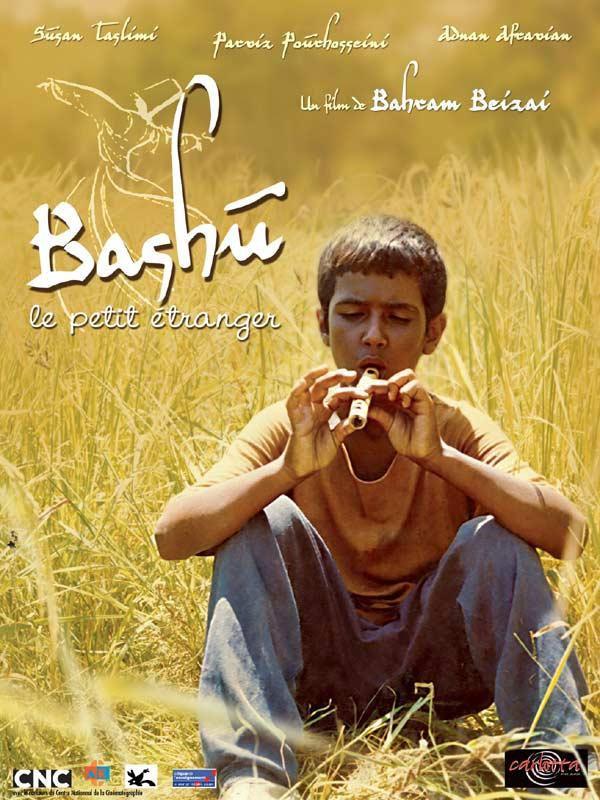

Amiro does not have the means to leave the wreckage of his own ship, but continues to struggle, hoping for a mental departure for a new space outside of his traumatic society. Amiro resides in the liminal space between the earth and the sea—in the ship—but the cause of his loneliness—his orphaning—and how he chose the wrecked ship as his shelter are never revealed. The key to this condition can be found in Beyzai’s Bashu: The

4 Similar trends involving the minimization of war were applied to other Iranian visual art forms. For more information, refer to “The Notion of Comics in Iran” by A. Ghaderi and E. Esfandi (2015).

MISE - EN - SCÈNE 09 Amir Barati

Fig. 10 | Amiro wins the ice in a competition in Naderi’s The Runner, 01:26:56. Center for the Intellectual Development of Children and Young Adults, 1984.

Little Stranger: its protagonist manages to leave his southern city behind and find peace in the north (Fig. 11).

Set in Iran in the midst of the country’s war with Iraq, Bashu recounts the story of a young boy named Bashu (Adnan Afravian), who escapes the war-torn Khuzestan province in southern Iran by taking refuge on the back of a cargo truck. Not knowing the truck’s destination, Bashu finds himself delivered to the ever-green and peaceful Caspian region in the rural north of the country, where there seems to be no sign of war. But as a traumatized character, Basha remains haunted by the consequences of war and his displacement. Bashu successfully sails away from the shores of the war zone, while Amiro stays in the wreckage of his ship. This choice to leave one’s home city or stay in its ruins is a conflict that haunts Amiro, but, apparently, he chooses to live within his city, directing his desire towards winning games and thereby representing his struggle to succeed in life. Bashu’s family has been killed during a bombardment, while Amiro’s family has disappeared from the film with no clues as to their whereabouts. The stray condition of Amiro suggests a traumatic past, with his family lost at an unknown time. Take, for example, the scene where Amiro looks at himself aboard his wrecked ship. His distorted image is portrayed in a triangular piece of mirror while he shows embarrassment. The shame stems from his failure to confront belligerent

children while collecting bottles at sea, and the subsequent reprimands of Amoo Gholam (Abbas Nazeri) who reproached Amiro for lacking the strength to defend himself against other children.

The broken mirror symbolizes the distorted image Amiro possesses of himself because of the social pressures he has faced. The mirror represents a broken Amiro, not because of failing at a competition, but because of a life moulded by broken social structures. The Lacanian mirror which should reflect a unified image of the self is broken, and therefore, he struggles to find his true subjective self through media images and magazines (Fig. 12).

Amiro never talks about his past or narrates his trauma; instead, he attempts to hide the central reasons behind his miseries, much like Naderi’s obscuring of war in the film. If Amiro had a family to support him, he might not have to work so hard to feed himself. He could have gone to school much earlier and would not have to tolerate being a social outcast. Consequently, he would have experienced a much more forgiving life. But the cause itself is absent. No social institution is there to support him against the unjust competition for survival, and few people show him mercy. This is most likely the result of a military confrontation that has shred the already traumatic social fabric of Amiro’s homeland.

This situation suggests the Freudian lack of transference when the subject cannot move away from its resistances, ultimately disabling it from verbally communicating their psychological struggles. When language lacks the proper power to describe an abundance of trauma and the subject cannot communicate its wounds, the subject appeases itself through bodily expressions of shouting and running. So, the competitions are repeated in different, unending forms. This repetition of fierce rivalry, in which being hit by a train or breaking a limb is possible, reveals one aspect of the lack of transference in a traumatized society. Shouting to airplanes and competing by tolerating the noise of the close-passing trains are signs revealing the veracity of traumatic experiences like war planes bombing civilians.

Explaining this mental process, trauma theorist Geoffrey Hartman writes, “Life seems always to be a matter of catching up, often unconsciously… Something in the present, therefore, may resemble (or reassemble) something forgotten, as if there were channels along which memory returns like a flood that hides its source. This is where uncanny sensations of repetition or correspondence make themselves felt” (546). The history in this film is effaced and reassembled through the events and games the children play. In this situation, as Dominique LaCapra also notes, one acts out past experiences when one’s relation to the present collapses. In such a condition, the temporality of experience is lost, and every current or past traumatic experience and rehearsals happens in the moment while facing fragments of the past. The only temporal aspects that are distinct from the present are the “future possibilities” that lie ahead of the traumatic subjects (699). That is exactly why, for Amiro,

Vol.07 No.01 | Spring 2022 10 Naderi’s The Runner : Trauma of Modernity and Desire for the Machine

Fig. 11 | Poster of Beyzai’s Bashu: The Little Stranger. Center for the Intellectual Development of Children and Young Adults, 1986.

there exists no past and everything happens in the present. His only hope is for a future in which he sails away from his current mental and social condition and finds a better world. However, he remains stuck living in the wreckage of the past and is not sure whether he can steer his vessel.

fact. It tries to make us believe the unbelievable; it demands the acknowledgement of being real, not only imagined” (541). Amiro attempts to embody his desires and victories in the competitions with other children. This imagination needs a factual atmosphere as well and thus, the airplane and the

Naderi is aware that modernity is a time of global engagement and that is why his hero Amir-o (Amir Naderi plus Hero) suggests a progressive protagonist who wishes to keep his independence while fully engaging with Others.

The only real power Amiro has at his disposal while living in war is to utilize his imagination and live in a world of his own constructed symbolism. When the social structure is fragmented and in no way fulfilling, Amiro recreates his own symbolic version of the world around him in order to operate. Regarding the structure of imagination, Hartman believes that “Imagination pursues a body—the body and atmosphere of

machine can be considered incarnations of the mechanistic atmosphere that embody his desires. Amiro joins others but follows his own dreams. He is not a total outcast, but his independence helps him operate better than others and thereby mature. He constantly pursues improvement and is a desired body in the traumatic modern world of Iran. He strives not to give into his traumas and wills to fight for escape.

MISE - EN - SCÈNE 11 Amir Barati

Fig. 12 | Amiro looking at the mirror in Naderi’s The Runner, 00:18:54. Center for the Intellectual Development of Children and Young Adults, 1984.

CONCLUSION

The Runner ultimately reveals the story of a community traumatized by modernity. This community views the charming face of modernity in the comfort and power produced by machines, yet this community lives in the shadows of the same machines. The modern machinery left bombs instead of prosperity. This condition—as well as the witnessing of the Other’s prosperity—coerces Amiro (as the symbolic hero of the film) and other children to use their bodies to compete with the machine, challenge its power, and instruct their bodies to operate like the machine, too. However, Amiro takes a different route to utilize machines to his own benefit by riding his bike. Riding a bike as a materialist symbol of early machinery versus a more sophisticated airplane best represents the condition of Iranians of the time: on the verge of modernization yet gripped by a devastating war.

While this traumatic society sees its “characters [finding] themselves oscillating between productive determination and destructive obsession” (Gadassik 480), the film does not wholly support the binary oppositions between the Orient and the Occident or the human and the machine. Naderi is aware that modernity is a time of global engagement and that is why his hero Amir-o (Amir Naderi plus Hero) suggests a progressive protagonist who wishes to keep his independence while fully engaging with Others. He protects his own desires, does not imitate other children, and knows that his desires are the desires (and tensions) of many other children of his time. So, rather than drawing borders and oppositional lines, he decides to educate himself to learn the discourse of the machine which has secured the Others their power and leisure. His competition turns out to be a successful one when he manages to read the full Persian Alphabet (in a region where the majority speak Arabic with southern Iranian accents) against the roaring engines of sophisticated airplanes.

While being sympathetic to the miseries of children in south Iran, Naderi propagates a politics of perseverance and goal-oriented diligence. He advocates for literacy and systematic education as a panacea to overcome the miserable conditions for children in a developing country in the 70s. But the key to his quest is finding a way to streamline the local literacy in order to provide the requirements for comprehending the discourse of modernity. He desperately attempts to represent a materialist approach where, through utmost diligence, local literacy can live side-by-side with modern machinery—it is a significant symbol of an imported modern discourse. This optimistic quest for synchronization of parallel ways of being (traditional and modern lifestyles) has made The Runner a unique product of Middle Eastern cinema. The idea that children of the machine age need to learn the discourse of the Other and the machine to adjust their local lives with this ontology is of unparalleled significance since it represented the mindset rampant in the 70s and 80s; it resulted in highly educated youths in Iran today. Yet Naderi’s hopes and dreams did not come true. The gulf between Western modernity and the traditional values of the local Middle

Eastern population has widened in the past decades and created innumerable tragedies in many Middle Eastern countries and the Islamic World.

Naderi also portrays the go-getter, semi-capitalist politics of rivalry which caused immense problems in Iranian society for years to come. The idea that the comfort of reaching the ice (as a sweet product of modern machinery) should be the aim of every child in a modernizing country proved problematic. During the 70s, the politics of fierce competition for personal gain at the cost of Others overwhelmed the traditional Iranian society which was mainly based on communitarian values. Despite the inevitability of rat-race social practices in modern cities, this mindset of the supremacy of personal gain introduced to Iranian society deep complications including brutal individuation, devalued ethical norms, economic corruption, and many more cultural, political, and economic conflicts that were not compatible with older communitarian systems of Iranian ethnic communities. Many years later, politics of social justice and equality replaced this outlook in Iranian cinema.

Vol.07 No.01 | Spring 2022 12

the

Naderi’s

The Runner : Trauma of Modernity and Desire for

Machine

Amanat, Abbas. Iran: A Modern History. Yale UP, 2019. Barati, Amir, and Razieh Eslamieh. “Ian McEwan’s Characters in Žižekian Process of Subjectivity A Study of Ian McEwan’s Atonement and Solar.” International Journal of Applied Linguistics and English Literature, vol. 4, no. 2, 2015, pp. 120-124, doi.org/10.7575/aiac.ijalel.v.4n.2p.120 . Accessed 2 Jan. 2022.

Bashu, the Little Stranger. Directed by Bahram Bayzai, performances by Firooz Malekzadeh, Susan Taslimi, Parvis Pourhosseini, and Farokh-Lagha Hushmand, Center for the Intellectual Development of Children and Young Adults, 1986.

Braves of Tangestan . Directed by Homayoun Shahnavaz. Performance by Mahmoud Johari, Shahrouz Ramtin, Kaveh Mokhberi, and Ali Akbar Mahdavifar. Iranian National Television, 1975.

De Planhol, X. “ĀBĀDĀN ii. Modern Ābādān,” Encyclopaedia Iranica, vol. 1, no. 1, 1982, pp. 53-57, www.iranicaonline. org/articles/Ābādān-02-modern. Accessed 03 May 2016.

Freud, Sigmund. Beyond the Pleasure Principle, edited by Ernest Jones, International Psychoanalytic Library, 1922.

---. Reflections on War and Death. Translated by A. A. Brill and Alfred B. Kuttner, Moffat, Yard and Co., 1918.

Gadassik, Alla. “A National Filmmaker without a Home: Home and Displacement in the Films of Amir Naderi.” Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East, vol. 31, no. 2, 2011, pp. 474–486, doi-org. proxy.library.umkc.edu/10.1215/1089201X-1264361

Accessed 2 Jan. 2022.

Ghaderi, A., and E. Esfandi. “The Notion of Comics in Iran.” Comics: Bilder, Stories und Sequenzen in religiösen Deutungskulturen. Kulturelle Figurationen: Artefakte, Praktiken, Fiktionen, edited by J. Ahrens, F. Brinkmann, and N. Riemer, Springer VS, 2015, pp. 204-233, doi. org/10.1007/978-3-658-01428-5_9. Accessed 2 Jan. 2022.

Gunning, Tom. “Chaplin and the body of modernity.” Early Popular Visual Culture, vol. 8, no. 3, 2010, pp. 237-245, doi.org/10.1080/17460654.2010.498161. Accessed 2 Jan. 2022.

Hartman, Geoffrey H. “On Traumatic Knowledge and Literary Studies.” New Literary History, vol. 26 no. 3, 1995, p. 537-563. Project MUSE, doi:10.1353/nlh.1995.0043. Accessed 2 Jan 2022

Kittler, Friedrich A., and John Johnston. Literature, Media, Information Systems: Essays. Routledge, 2012.

Lacan, Jacques. The Seminar of Jacques Lacan: Book II. Translated by Sylvana Tomaselli, edited by Jacques-Alain Miller, Norton, 2011.

---. The Seminar of Jacques Lacan: The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis (Book XI). Translated by Alan Sheridan, edited by Jacques-Alain Miller, Norton, 1998.

LaCapra, Dominick. “Trauma, Absence, Loss.” Critical Inquiry, vol. 25, no. 4, 1999, pp. 696–727. proxy.library.umkc. edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=mzh&AN=0000315474&site=eds-live&scope=site. Accessed 2 Jan 2022.

Malabou, Catherine. The New Wounded: From Neurosis to Brain Damage. 1st ed, Fordham UP, 2012.

Motaqedi, Robabeh, et al. “Oil Industry and Development of Population and Occupation in Oil Rich Regions in the South of Iran.” Researches on Social History, vol. 3, no. 2, 2014, pp. 121-137. search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edsdoj&AN=edsdoj.0367be6200714620b6fe90b25d7d2ed5&site=eds-live&scope=site. Accessed 2 Jan. 2022.

Naficy, Hamid. A Social History of Iranian Cinema. Duke UP, 2011.

The Runner. Directed by Amir Naderi, performances by Abbas Nazeri, Majid Niroumand, and Musa Torkizadeh. Center for the Intellectual Development of Children and Young Adults, 1984.

Tangstir. Directed by Amir Naderi, performances by S. Chubak, Nemat Haghighi, Enayat Bakhshi, Parviz Fanizadeh, Jafar Vali, and Behrouz Vossoughi. Ali Abbasi, 1973.

Zeydabadi-Nejad, S. “Iranian Intellectuals and Contact with the West: The Case of Iranian Cinema.” British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies, vol. 34, no. 3, 2007, pp. 375–398. www.jstor.org/stable/20455536. Accessed 2 Jan. 2022.

MISE - EN - SCÈNE 13 Amir Barati

WORKS CITED

The End of Everything

Millennium Anxiety in Gregg Araki’s Nowhere

BY HENRIQUE BRAZÃO Independent Film Scholar

ABSTRACT

With its idiosyncratic cinematic language, Nowhere (1997), directed by indepedent American filmmaker Gregg Araki, notably conveys a sense of acceleration and anxiety associated with the impending turn of the millennium. One of the film’s many fast-paced sketches—showing a young couple ending their relationship—serves as a corollary of a doomed generation caught in the vortex of rampant technological development in an era of excess and disposable emotions. Through sound, framing, and editing—and involved in the context of Y2K concern and Christian eschatology—Araki creates a universe where nothing is permanent, where everything ends.

Gregg Araki’s film Nowhere (1997) pulsates with the energy of transgression. Like its predecessors, this chaotic example of independent cinema reveals a profound conscience of cinematic conventions while simultaneously rebelling against those formalities. A particular scene—showing two characters ending their tumultuous relationship—highlights the concept of “millennium anxiety,” a much-discussed (and somewhat abstract) notion imbued in media and cultural conversation throughout the 1990s, connoting a collective sense of uncertainty about the symbolic arrival of the third millennium.1

Nowhere is the final piece of a trilogy known as “the teenage apocalypse trilogy” (Hart 33) and arguably the most apocalyptic manifestation of the group. The film displays a mosaic narrative with an ensemble cast, featuring the protagonist Dark (James Duvall), an eighteen-year-old college student who believes his death is impending. Many young characters with one-word nicknames like Egg (Sarah Lassez), Lucifer (Kathleen Robertson), Mel (Rachel True), Zero (Joshua Gibran

Mayweather) or Ducky (Scott Caan), populate this frenetic and hyper-saturated universe. Set in Los Angeles during a single day, Araki’s film does not present a discernible classical narrative arc, favoring chaos and fragmentation over causality. Throughout the day, the connections between the parts are established through fast-paced sketches—almost all of them invariably flooded with diegetic music— that show the characters’ interactions while addressing a torrent of issues, such as sexual awakening and orientation, relationship boundaries, eating disorders, drug abuse, religious fanaticism, celebrity culture, existentialism and, ultimately, the end of the world. A party held during the evening becomes the convergence point where all the subcultures collide, and where fragile egos—underdeveloped teenage personalities struggling for affirmation—break. Through the deaths of two characters and the alien abduction of a few others, the film conveys a melancholy theme of impermanence in an erratic time and place, thereby producing a bleak portrait of a (doomed) generation that cannot help but accept the end of everything. The ending that these

1 The term “anxiety” is loosely employed here, considering its colloquial expression rather than its strict medical definition.

Vol.07 No.01 | Spring 2022 14

FEATURETTE

(purposefully) one-dimensional characters collectively experience coincides with the end of the century, mainly defined by abrupt technological changes and the apprehension over the Y2K phenomenon.2

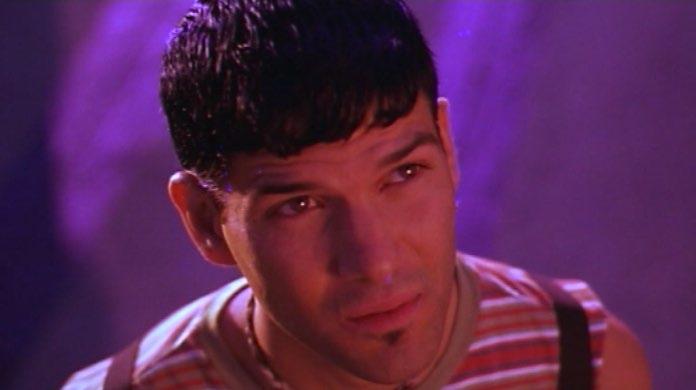

Despite the film’s coherent sense of aesthetic identity, the scene in question is detached from the main narrative because of its unique traits (Fig. 1). Most notably, the formerly omnipresent music is replaced by remote, indistinct traffic sounds, and the sardonic tone of the dialogue is suspended, making way for vulnerability and introspection to emerge.

Running slightly over one minute, the scene consists of four different camera positions, resulting in twenty-one editing shots. The shot/reverse shot dialogue is enclosed between two establishing shots, with opposite tracking movements, and there is an isolated insert of a dirty hand. This conventional approach to scene construction, a strong legacy of Classical Hollywood, is subverted by the number of cuts—it is closer to music video standards than that of narrative cinema— where the accelerated rhythm underscores the substance abuse subtext. The action is minimal: Cowboy (Guillermo Diaz) arrives at what is possibly the fringes of a highway, where his heroin-addicted boyfriend Bart (Jeremy Jordan) lies, after injecting himself. Cowboy wants to make an ultimatum. The

low angle long-shot that opens the scene shows the silhouettes of the characters against a bright purple sky. Bart rests on a metal structure from the back of a hotel advertisement, where a neon heart and the word “rooms” can be seen. The framing gives the impression that the tip of the heart-shaped sign rests right above Bart’s chest. Colourful yet unclean, the shot contrasts the visual noise of the metal girders and the tranquility of the chromatic scheme, particularly the violettinted sky. This idealized, abstract portion of the city echoes the film’s off-screen opening line, spoken by Dark: “LA is like, nowhere. Everybody who lives here is lost” (00:00:15-00:00:18).

Nowhere’s Los Angeles is an amalgam of colours and textures with few (if any) recognizable locations. It is an assembly of non-places (Augé 76), and the characters are as lost and disjointed as the spaces around them.3

A visibly concerned Cowboy (Fig. 2) confronts his boyfriend and tells him he can no longer deal with his addiction. The dynamics of the dialogue are established by the camera angles and framing. Cowboy, disappointed and mournful, appears smaller and therefore powerless, while Bart is seen from Cowboy’s point of view, on an unsettlingly tight close-up, with his head upside down (Fig. 3). After hearing his lover’s threat, Bart, whose reactions are manifestly slow and apathetic,

2 The Y2K problem, or “the year 2000 bug,” was a widely held concern that, at the end of 1999, computers would not be able to compute the abbreviation 00 in 2000 and would cause a massive collapse in information systems around the world. Except for a few minor occurrences, the transition was uneventful (Tapia 267).

3 The concept of non-place, as defined by French professor of anthropology and ethnology Marc Augé, considers technological development and globalization to produce a discourse about the relations individuals establish with the proliferation of modern transient areas, like highways, shopping malls, or airports (Augé 76).

MISE - EN - SCÈNE 15 Henrique Brazão

Fig. 1 | Still from the opening scene of Araki's Nowhere, 00:24:17. UGC, 1997.

makes a vague promise to get sober and extends an unkempt hand (Fig. 4). Cowboy ignores the gesture and leaves the scene. In a film with a considerable amount of close-ups, the dirty hand consolidates an aesthetic strategy that reveals the tactile dimension of the moving image.4 In various scenes, the protagonist uses a video camera that produces grainy, low-resolution pictures (Figs. 5 and 6) that entail haptic visuality qualities (Marks, Touch 3). Here, the brief insert of the hand—a direct reference to the haptic—not only alludes to the possibilities of

film as a multi-sensory medium but also invigorates the narrative: Bart’s gesture is a cry for help, or a thin vestige of love wherein the dirt straightforwardly describes the character’s deplorable circumstances.

As the micro-romantic tragedy unfolds, the film—whose prevalent nonverbal discourse is filtered here through Cowboy’s perspective—makes a moral statement against excess. Isolated and geometrically confined between strict lines, Bart embodies the consequences of succumbing to a lifestyle of continuous self-destruction. For less than three seconds, the wistful image of his abandoned body pauses the turbulence of the plot. Apart from this small glimpse, there is no time for contemplation in Nowhere. Static moments are rapidly consumed by the film’s voracious pace, leaving the spectator longing for breathing space.

A state of anxiety affects the film’s diegetic world as much as the viewer. As previously inferred, the editing, mise-en-scène choices, and the actors’ crude performances contribute to the construction of a meaning that is symptomatic of the cultural and social context surrounding the production and release of the film as a cultural object (Bordwell and Thompson 62-63). Focusing on the examined scene and its bizarre aftermath—Bart commits suicide after being encouraged by a televangelist—the degradation of life caused by external forces (drugs, television, urban geography, alienation) mirrors the general attitude and anxieties regarding the anticipation of the year 2000. The religious undertones related to the fates of these young people directly evoke Christian eschatological discourses and the numerical and chronological importance of the arrival of the third millennium (Tapia 269). Scholarly discussion about this symbolic transition tends to address a “felt condition that unsettled a naturalized sense of temporal and historical progression” (Balanzategui 68), or, as put forward by Jean Baudrillard, the idea of the year 2000 was even associated with “terror” (9). With his provocative trilogy—especially with its conclusion—Araki has delivered a peculiar portrait of unsettling times, best observed two decades later, with the privilege that time allows.

If the nihilistic approach to the inevitability of death defines the ethos of Nowhere, a more concerned (and openly pessimistic) mindset related to millennial distress surfaces sporadically. Bart and Cowboy’s moment—with its minimal dialogue, the asymmetry of the characters’ positions, the messy advertisement-like surroundings, the frantic succession of shots, and the overall troubled mood—epitomizes this atmosphere of apprehension and, along with many other instances, makes Nowhere a product of its time, a memento mori for the twentieth century.

4 As studied by authors like Canadian film and media theorist Laura U. Marks, the moving image is capable of generating sensory responses beyond sight and sound. For the author, touch or smell are effectively stimulated by audiovisual content (Marks, The Skin of the Film 2).

Vol.07 No.01 | Spring 2022 16 The End of Everything: Millennium Anxiety in Gregg Araki’s Nowhere

Fig. 3 | Low-angle shot of Bart from Araki’s Nowhere, 00:24:33. UGC, 1997.

Fig. 4 | Bart extends his dirty hand in Araki’s Nowhere, 00:24:50. UGC, 1997.

Fig. 2 | Cowboy confronts Bart from Araki’s Nowhere, 00:24:21. UGC, 1997.

WORKS CITED

Augé, Marc. Non-Places: An Introduction to Supermodernity . Translated by John Howe, Verso, 2008.

Balanzategui, Jessica. “The Uncanny Child of the Millennial Turn.” The Uncanny Child in Transnational Cinema: Ghosts of Futurity at the Turn of the Twenty-First Century, Amsterdam UP, 2018, pp. 67-92, doi.org/10.2307/j. ctv80cc7v.6. Accessed 15 Dec. 2021.

Baudrillard, Jean. “Pataphysics of the Year 2000.” The Illusion of the End. Translated by Chris Turner, Polity Press, 1994, pp. 1-9.

Bordwell, David, and Kristin Thompson. “The Significance of Film Form.” Film Art: An Introduction, 8th ed., McGrawHill, 2008, pp. 53-73.

Hart, Kylo-Patrick R. Images for a Generation Doomed: The Films and Career of Gregg Araki. Lexington Books, 2010.