Text

3 Soledad, Rocio Bravo '10 4 Most of the Way, Lily Meyer'13 10 Social Capital, Alejandra Ceja '12 12 Winter Out, Ayoosh Pareek '12 14 Shadow of Shame, Esther Escotto 17 Ya no queda nada, Juan Ruiz '12 18 A las horas del agua, Sara Mann'10 20 Tus manos, Rocio Bravo '10 22 Sin Ti, Rocio Bravo '10 24 I Heard the Ocean Call My Name, Margie Lane 26 Las Paraguas Del Mar, Sara Mann'10

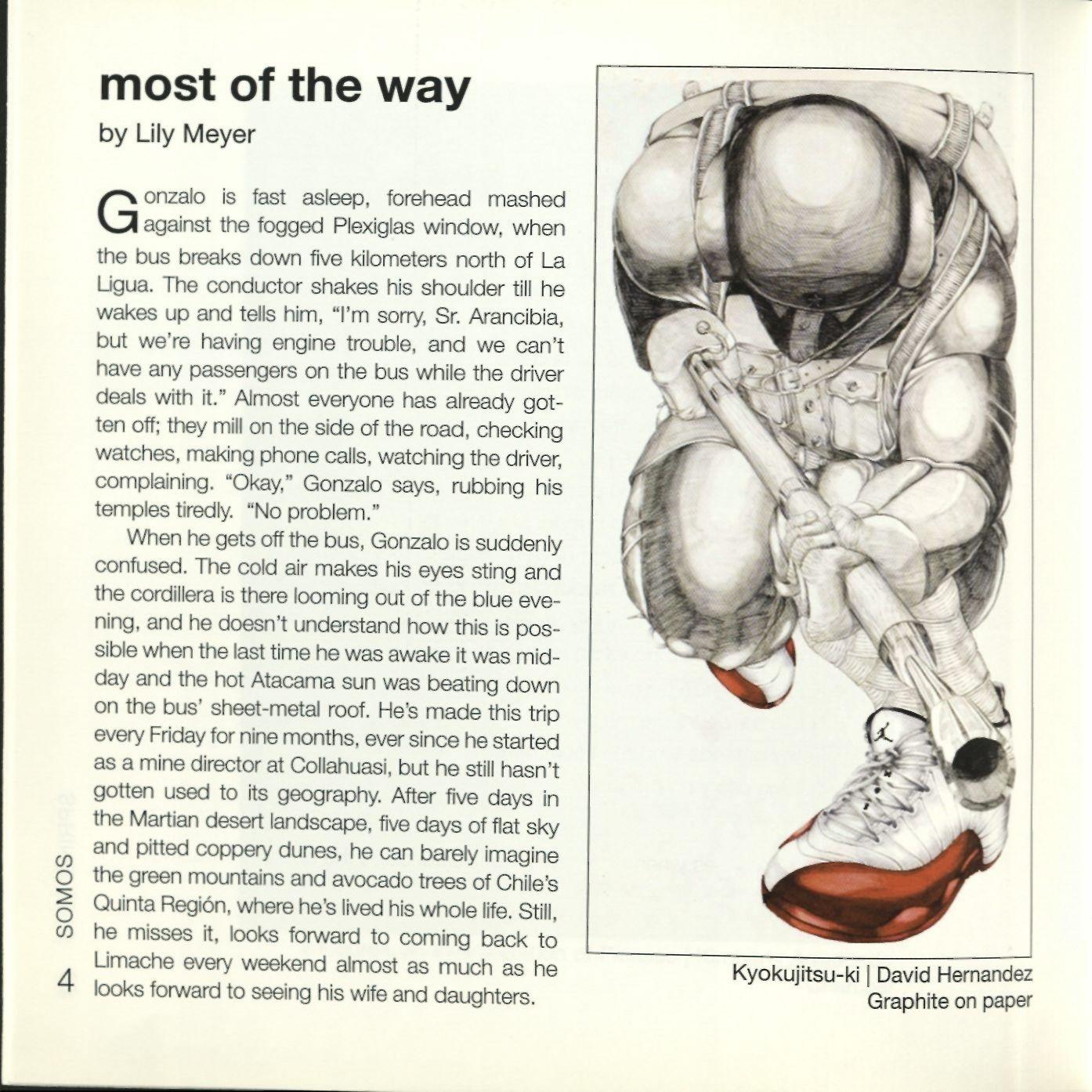

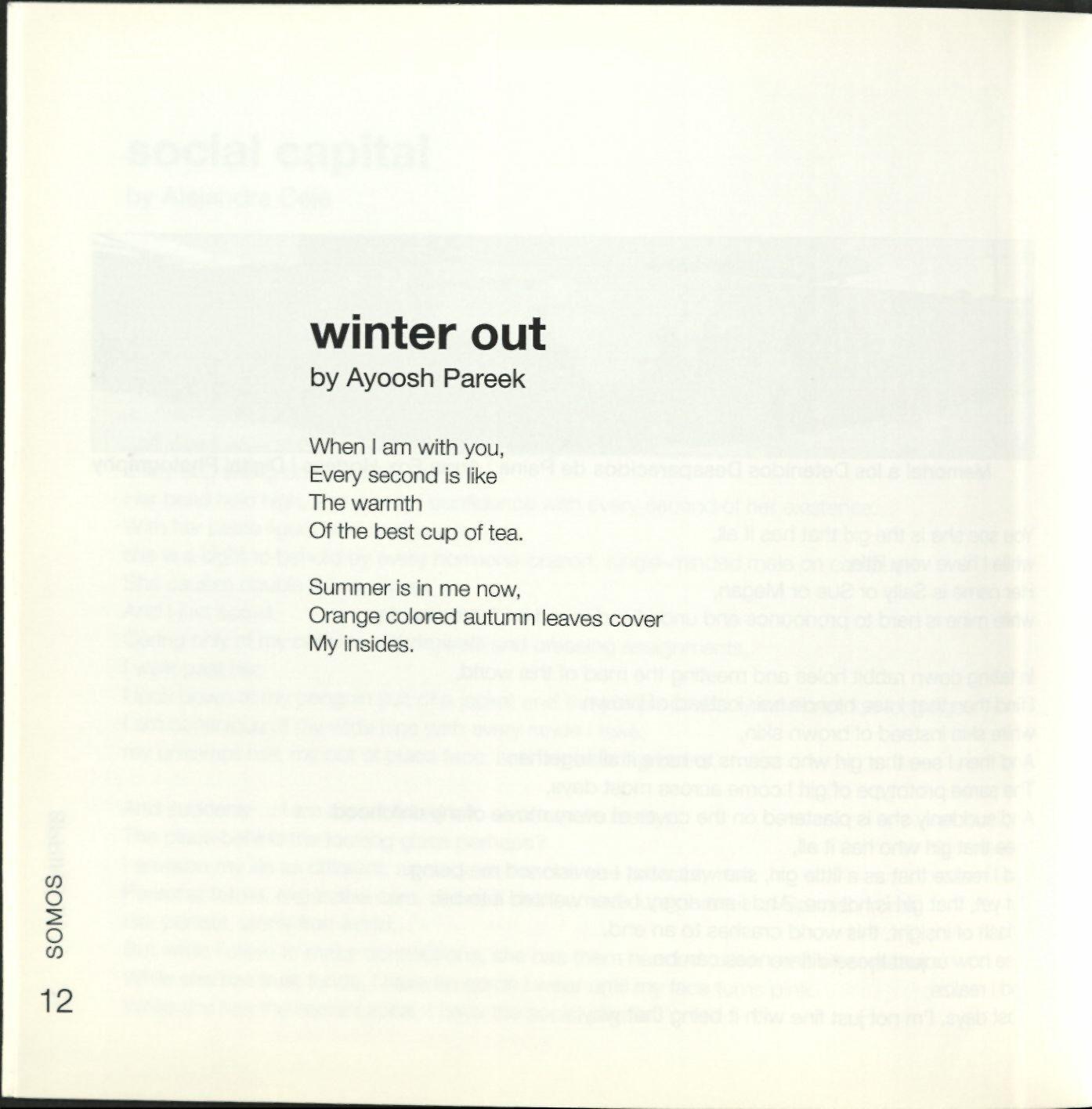

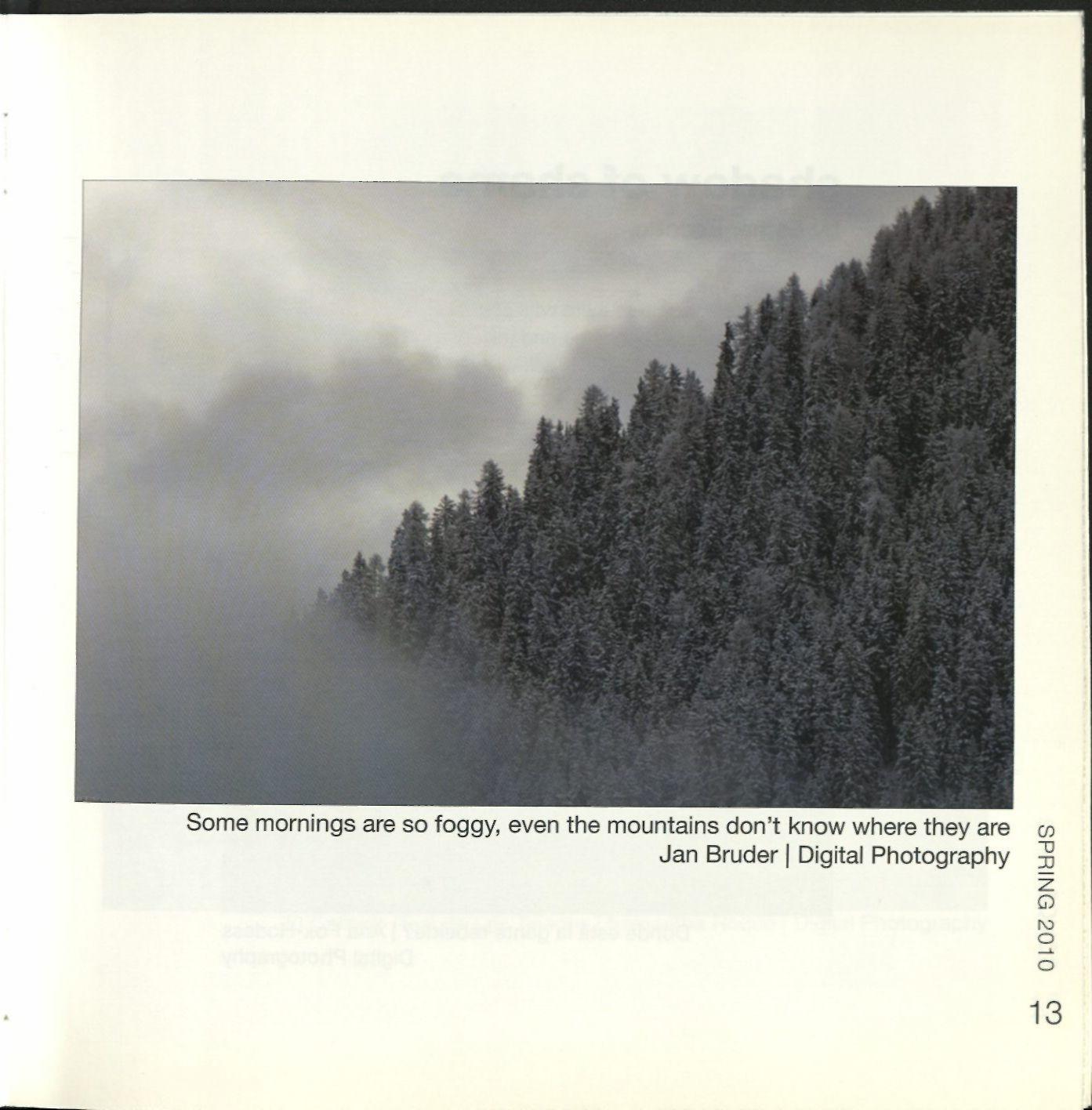

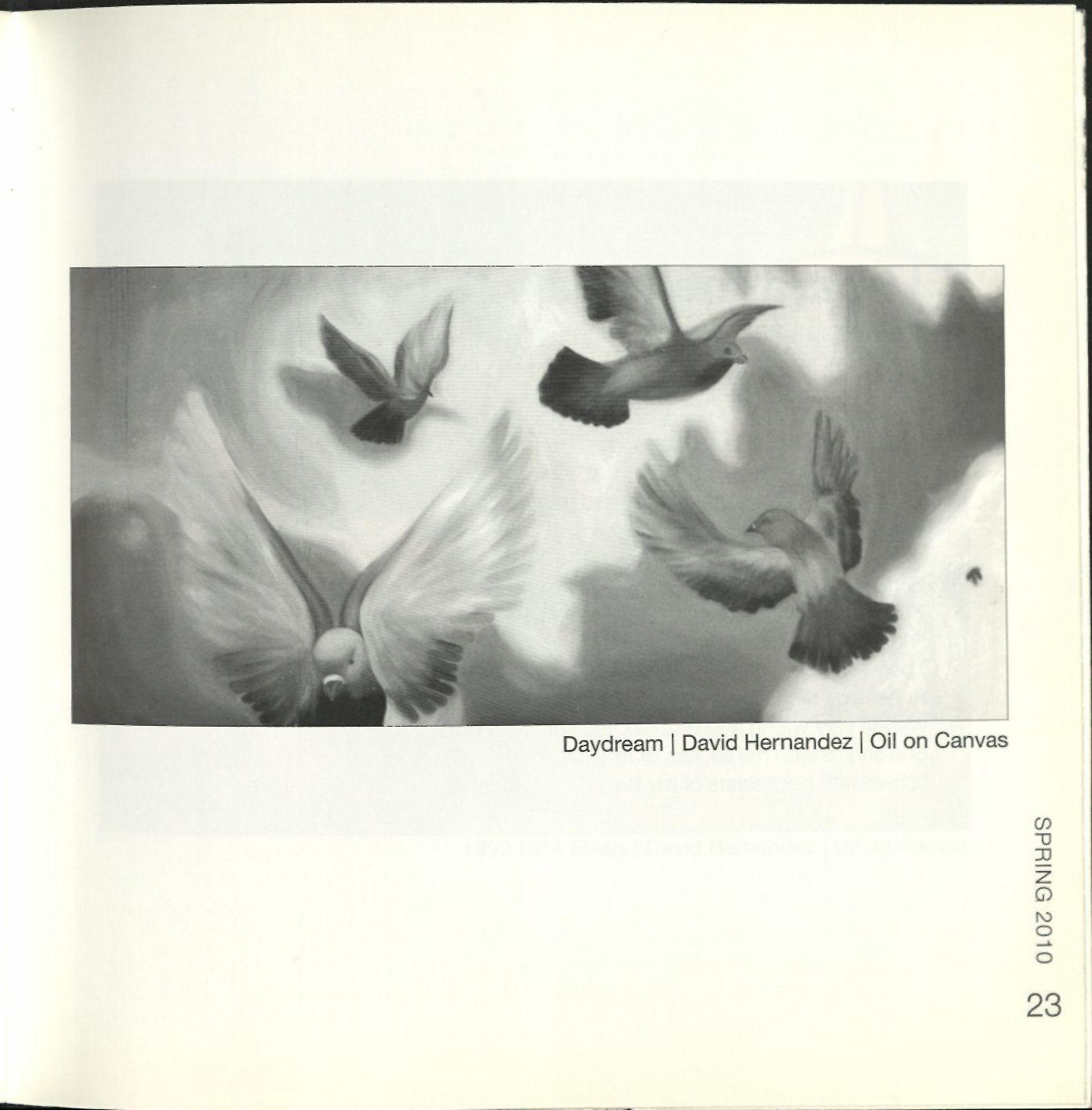

2 2 Figures, an Interpretation of Picasso, Kimberly Arredondo '11 4 Kyokujitsu-ki, David Hernandez '11 8 Del maguay, Samantha Roque'10 11 Memorial a los detenidos desaparecidos de Paine, Ana Fox-Hodess '10 13 Some mornings are so foggy, even the mountains don't know where theyare, Jan Bruder '10 14 Donde esta lagente rebelde?, Ana FoxHodess '10 15 El camino real de los tejanos, Samantha Roque '10 16 Chiapan Lullaby, Samantha Roque '10 23 Daydream, David Hernandez '11 25 1992 NBA Finals, David Hernandez '11 27 El sueno (Memorial a VioletaParra), Ana Fox-Hodess '10

ngures, an Interpretation of Picasso | Kimberly Arredondo Charcoal

ngures, an Interpretation of Picasso | Kimberly Arredondo Charcoal

by Rocio Bravo

by Rocio Bravo

Estoy parada en miedo de la calle. La lluvia cae fuertemente sin piedad. No siento el agua sobre mi piel Ni el frio sobre mi cuerpo. Estoy viendo el mundo pasar. Lo quiero detener y no puedo. Quiero gritar pero no se mueve mi boca. Quiero correr pero no responden mis pies. Estoy parada en el silencio de lanoche. El agua cae pero no ya no me moja. No siento nada porque no existo. Nadie me ve, nadie me siente. Estoy gritando y no me escuchan. la lluvia cae y no me toca.

by Lily Meyer

by Lily Meyer

Gonzalo is fast asleep, forehead mashed against the fogged Plexiglas window, when the bus breaks down five kilometers north of La Ligua. The conductor shakes his shoulder till he wakes up and tells him, "I'm sorry, Sr. Arancibia, but we're having engine trouble, and we can't have any passengers on the bus while the driver deals with it." Almost everyone has already gotten off; they mill on the side of the road, checking watches, making phonecalls, watching the driver, complaining. "Okay," Gonzalo says, rubbing his temples tiredly. "No problem."

When hegets off the bus, Gonzalois suddenly confused. The cold air makes his eyes sting and the Cordillera is there looming out of the blue evening, and he doesn't understand how this is possible whenthe last timehe wasawake it was midday and the hot Atacama sun was beating down on the bus' sheet-metal roof. He's made this trip every Fridayfor ninemonths, eversince hestarted as a mine director at Collahuasi, but he stillhasn't gotten used to its geography. After five days in the Martian desert landscape, five days of flat sky ^ and pitted coppery dunes, he can barely imagine O the green mountains andavocado trees of Chile's ^ Quinta Region, wherehe's livedhis whole life. Still, co he misses it, looks forward to coming back to Limache every weekend almost as much as he 4 looks forwardto seeing his wife and daughters.

Kyokujitsu-ki | DavidHernandez Graphite on paper"Permiso," someone says, tapping him on the shoulder, and heturns to see aflat-faced, chubby woman holding a huge glass jar of pickled olives in one arm. "Do you have a cell phone I can borrow?" she asks.

"In a minute, all right? I have to call my wife." She thanks him and steps back discreetly, and he fumbles his phone out of his pocket, pressing keys without needing to look. Maqueta answers on the first ring and doesn't bother to say hello. "Are youin Quillota yet?"

"No, the bus broke down outside La Ligua, and no one knows how long we'll be stuck here. I don't think we'll be in Quillota before ten at the earliest, andthenI'll haveto waitfor themicro, and you know the one that goes to Limache doesn't come that often."

"Pucha, Gonzalo," she says,and hecan imagine her rolling her almond eyes and scowling at the floor. "The girls havebeen talkingall day about how Papi's coming home, and now you won't be back until after they're asleep? That's shit. I bet there wasn't any breakdown. I bet you missed your bus because you were busy fucking your desert woman."

"You know there'sno suchwoman, and I can't help that the bus is going to be late. Tell Paula and Violeta I'll come give them kisses when I get home."

"You want to wakethem up?" Maqueta snaps, and Gonzalo can't help laughing a little—he's used to getting yelled at, to Maqueta pretending she's angry at him instead of at his absence.

This separation has turned them both back into moody, horny teenagers, complaining and bickering on the phone for hours during the week and pouncing on each other like puppies every weekend. "Calmate, mujer, it's just a few hours' delay. Tell the girls whatever you want. I'll see you tonight, okay? I love you."

"I love you too.Oh, and Gonzalo?"

"Yes?"

"If Anglo American doesn't transfer you back to the mine here in December like theypromised, either you're quitting your job or we're getting a divorce." She hangs up, and he shakes his head tiredly. Even though he knows Maqueta doesn't mean any of her threats, she makes them almost every day now, and he can't help worrying a little. He looks around for the woman with the olives, but she's borrowed someone else's phone and is arguing with whoever's on the other end, stamping her feet andtwisting her mouthangrily. Maybe she hasn't seenher husband sinceSunday either, he thinks.

The driver can't fix the engine, and after an hour a different bus comes and everyone hauls their bags and boxes aboard; it pulls into the station in Quillota's main plaza just after ten-thirty, w almost three hours late. Gonzalo grabs his back- J pack andbounds off the bus to call Maqueta,but z this time she doesn't pick up, and he leaves a ^ message saying only, "I'm most of the wayhome, o I love you." At firstthe passengers standin amass o on the sidewalk, complaining to each other and looking around for the husbands or wives or taxi 5

drivers who are supposed to pick them up, but one by one the rides come and soon Gonzalo is there alone. He's resigned to a long wait—Quillota's little microbuses are unreliable even during the day, and after sundown the one to Limache, which is forty-five minutes away, runs every second hour at best.

The only other people in the plaza are agroup of teenagers roughhousing and eating and occasionally breaking into pairs to kiss aggressively. They all have the same tight jeans and pierced lips and angry hair slanting into their eyes, and Gonzalo can barely tell which ones are boys and which girls; he wonders what he would do if his little daughters turned into kids like these. He can't believe that they will, though. He can barely believe that they're going to grow up at all, but it seems like Violeta, his six-year-old, is another centimeter taller every weekend, and three-yearold Paulacan say more every time he talks to her on the phone. When he called home yesterday evening, she said, "Today I saw a purple flower and Mami said it has the same name as Violeta, but what about the Paula flower? It's more pretty, right? and he almost cried. There's no way, he tells himself, that she could ever look like this. He feels like an old man, watching them and disapproving, but he can't help wanting to walk across w the plazaandsay: Fix your hair, takeall that ridicu-

O lous metalout of your faces, andlearn how toact.

^ You're going tobe adults soon, you know.

As if he could read Gonzalo's mind, a boy with blue-tipped hair and a ring through the mid-

O die of his nose takes a final bite of the chicken

leg he's been gnawing and flings it towards him, making the entire group burst out laughing. The bone skids greasily to a stop in front of Gonzalo's bench, and within secondstwo stray dogsbound out of the darkness,claws scrabbling onthe concrete, and pounce on it. For a second they play tug-of-war, but thesmaller dog, arangy black animal with a pointed nose and only one ear, quickly wins the drumstick, and the other, which is so big and shaggy it has to be part wolf, clamps its teeth around the black dog's neck instead. They roll in front of Gonzalo, snapping and snarling, and he pulls his feet onto the bench protectively

and looks for a branch or rock to throw at them. There's nothingaround, though,andso hewatches as the wolf-dog flips the black dog onto its head, sending thebone flyingout of itsjaws. Both dogs leapfor it, butthis timethe wolf-dog isfaster by aninstant: it grabsthe drumstickand theother dog latches onto its throat instead.They're under a streetlight, and Gonzalo can see blood glistening aroundthe blackdog's teethand inits matted neck fur; it's a tie, he decides, they should share the bone. Instead,though, the wolf-dogclubs the

tfHe can barely imaginethe green mountains and avocado trees of Chile's Quinta Region, where he's livedhis whole life, JJ

other with its heavy front paw and the black dog falls away. It twists in the shadow, trying to lick the cuts between its shoulder blades as the wolfdog gulps the bone down in two huge snapping bites. When thewolf-dog hasfinished eating, they both shakethemselves and lope,almost together, down the street. Gonzalo twists to watch them and to look for the micro, which of course isn't coming, and whenhe turnsback there's awoman standing in front of him.

"Can I help you?" he asks politely, and she purrs, "I don't know, m'ijo, can you?" and he knows immediatelythat she's a whore.He's alittle surprised—Quillota's a quiet town, and a conservative one even by Chilean standards, and so the putas generally stay inside and let men come to them. Gonzalowent toabrothel once,thenight he graduated from high school, and he remembers the girl he was withthat time looking alot like this one: same glossy black hair, same heart-shaped mouth, same hungry eyes,and samehuge chest. He knows it's been thirteen years and she must be saggy and worn out by now, but something in him insiststhat thisis thesame woman,and so he asks, "What's your name?"

"Yesica." It's not her, of course, and his chest tightens sadly. "What's yours?"

"I'm Gonzalo."

"Well, Gonzalo,"—she stretches his name out, breathing through the vowels—"what are you doing out here all alone?"

"Waiting for the microto Limache."

"All the wayto Limache?That could be hours, and you'll get so cold! Aren't you cold already?"

she asks, and leans over to rub his arms, giving Gonzalo aperfect view down her shirt toher tetas spilling out of her white lacebra. He doesn't want to look,and hedoesn't want tocompare herbody to Maqueta's, to imagine how different and new her breasts would feel in his hands, but he does, and evenas theblood rushesbetween hislegs he feels a knot settling in the hollow of his throat. "I don't mind the coldmuch," he says.

"Well, I just hate it. Look, why don't we go somewhere warm, just for a little while?" She cocks a thinly plucked eyebrow at Gonzalo, and he raises one back at her and realizes with asudden rush of adrenaline that he wants to say yes. It's been a long day and he's annoyed with the teenagers across the plaza and waiting for the micro and the bus breakdown and traveling, and he wants to go with Yesica, if that's even her real name, and clear his head for two or three lucas. Still, he's a marriedman, and sohe says, "I'm sorry, but I'mwaiting for themicro, remember? Ihave to stay in the plaza."

"Oh, my room's just above the empanaderia," she says, pointing across the street at a brightly lit shop with a blackboard in the window listing the twenty different kinds of empanada they have that day. "You'd be able to see the micro out the w window easily." J

"Well, all right," Gonzalo says slowly, still look- ^ ing at the empanaderia instead of into Yesica's ^ face. She puts her long-nailed thumb under his o chin delicately and tips his face towards hers; he o expects her to kiss him and isn't sure whether he'd like her to or not, but instead, she says, "Are 7

you hungry?" He nods and suddenly thinks: this can bemy test—I'llget an empanada, buyone for her too, and ifthe micro doesn't comewhile we're eating, I'llgo up toher room fora little bit.Then it's just chance, and chance is fair. Besides, I'll make it fast with her, and then I'll be better, slower, for Maqueta tonight. "Let's go get empanadas," he says, standing up. "My treat."

There's only oneperson workingthis lateat the

empanaderfa, an old woman who speaks with a southern Chilean accent and collapses her face into a pouchy scowl when they come in, but she brings them empanadas—de queso for Yesica, de pino for Gonzalo—still hot from the oven and tells them without inflection to have a nice night. "Sad old bag," Yesica comments as they step back outside, crunching into her empanada hungrily. Ropes of white cheese stretch between the

dough and her mouth, smearing her lipstick and leaving a trail of grease on her chin; her appetite attracts Gonzalo, and he bites into his own empanada, wanting to finish it quickly. The filling is different from the pino that Maqueta makes—the olives and eggs and raisins are chopped into the ground beef instead of mixed in whole—and he doesn't like it as much, but it's more than good enough forright now. Hecloses his eyesfor amoment to enjoy it, a habit of his with both food and sex, and when he opens them the micro to Limache is at the far end of the plaza.

For a split second Gonzalo is angry, wishes it had come twenty minutes earlier or twenty minutes later, but before the thought's even formed he's already running towards the micro. He can hear Yesicachasing afterhim,high heelsclacking, calling out with her mouth full, "Wait, we haven't had any fun yet," but he ignores her. The driver is already flickering the headlights, signaling that he's about to start, and Gonzalo flails his arms and makes himself run faster, knowing that this is the last one to Limachefor the night.If he doesn't get on this micro, he won't get to be with Maqueta tonight. He won't get to wake his daughters up early in the morning to juice oranges and fry eggs for them like he always does on Saturdays. He'll have to spend the night in a whore's room abovethe Quillotaplaza, andnow hecan't believe that he ever wanted to go there at all. He can see into the micro now, and he waves his arms to attract the driver's attention in the rearview mirror. The half-eaten empanada flies out of his grasp,

but the doors stay open and he grabs the rail on the side of the micro with his greasy hand and swings himself inside, and as soon as he's firmly on the stairs the driver closes the door and shifts into gear. "Thank you," Gonzalo pants, "thankyou very much, senor," and the man smiles and says, "All the way to Limache, no?"

"That's right," Gonzalo says, slipping a tenpeso coin into the fare box. "How'd you guess?"

"You lived closer in, you wouldn't haverun like that." He laughs, and as Gonzalo settles into a seat he pictures himself sprinting to the micro, how desperate he must have looked—how desperate he was. He glances out the foggy window and sees Yesica curled on a bench with her shoulders hunched and chin tucked in like a cat, watching something in front of her. At first he can't see what she's looking at, but as the bus rounds the corner the headlights sweep over the plaza and Gonzalo sees the black dog and the wolf-dog fighting again. The wolf-dog has something clenched tightly in its jaws and is whipping its shouldersback and forthto shakeoff the black dog, which has dug its teeth deep into the bigger animal's hackles. They're moving in a slow, shaky circle, and as they come close to Yesica she w stretches, stands,and kneesthe blackdog off the J wolf-dog. Both of them run away, past the micro ^ and into the street, and as they go by Gonzalo G) sees his half-eatenempanada grippedin thewolf- o dog's teeth. Yesica looks at them and then at the o micro and Gonzalo waves at her half-heartedly; she doesn't wave back, but from the look on her 9 face he's sure that she noticed.

by Alejandra Ceja

by Alejandra Ceja

Mine is somewhat rigid, frizzy, and difficult to manage. Hers is light, soft, and TV-commercial shiny. The early unforgiving light exposes my tired eyes and groggy demeanor. I slouch with abag of books plastered on my back, apathetic but on edge. She walks around erect, her long hair blowing in the wind, a tiny bag sitting on her shoulder...

Her head held high, she exudes confidence with every second of her existence. With her petite figure and designer jacket, she is a sight to behold by every hormone-crazed, single-minded male on campus. She causes double takes, stares... And I just scowl.

Caring only of my caffeine withdrawals and pressing assignments, I walk past her.

I look down at my penguin suit of a jacket and the jeans I probably wore not too long ago. I am conscious of my wide hips with every stride I take, my unkempt hair, my out of place face, and my wearing boots.

And suddenly ... I am transformed into an alternate reality, The place behind thelooking glass perhaps?

I envision my life as different, as easy, as the one she probablyhad.

Personal tutors, expensive cars, nannies she learned cute phrases of Spanish from. Her perfect, worry free world...

But while Istrive to make connections, she has themhanded to her on asilver platter. While she has trust funds, Ihave an apronI wear until my faceturns pink. While she has thesocial capital, Ihave the social stigma.

You see she is the girl that has it all, while I have very little. Her name is Sally or Sue or Megan, while mine is hard to pronounce and underlined in red on thecomputer. In falling down rabbit holes and meeting the mad of this world, I find then thatI seeblonde hair instead of brown. white skin instead of brown skin. And then I see that girl who seems to have it all together, The same prototype of girl I come across most days, And suddenly she isplastered on the cover of every movie of my childhood. w I see that girl who has it all, "o and Irealize that as a little girl, she was what I envisioned me being. But yet, that girl is not me. And I am angry I ever wanted it to be. ® A flash of insight, this world crashesto an end, o I see how unjust these differences can be, o And Irealize most days, I'm not just fine with it being that way.

Fox-Hodess | Digital Photography

Memorial a los Detenidos Desaparecidos de

Fox-Hodess | Digital Photography

Memorial a los Detenidos Desaparecidos de

by Ayoosh Pareek

by Ayoosh Pareek

When I am with you, Every second is like The warmth Of the best cup of tea. Summer is in me now, Orange colored autumn leaves My insides.

Some mornings are so foggy, even the mountains don't know where they are w

Some mornings are so foggy, even the mountains don't know where they are w

by Esther Escotto

by Esther Escotto

Let there be light where there was shame

And its shadow shall be lifted and raised up

And it will stretch and writhe itself

In sodden and broken pieces, it will fall to the ground

Where crevices that harbored the eveil will welcome its own

Ya no queda nada sino recuerdos y memorias de amores ciegos, trayectorias de horas congeladas, pasmadas.

Ya no queda nada sino los vientos y los truenos que atormentaron nuestros suerios y vaciaron tu mirada.

Cantan las fantasias del pasado del olor de las hortensias y van corrompiendo mi demencia con su brio porfiado.

Las lunas blancas adornanmi soledad; el Eden que sonaba con alcanzar y al que me humillo esperar no irrumpenada sino la verdad.

by Sara Mann

by Sara Mann

Me dijiste una vez que estaba todo dentro de la palabra. Extranar: la exportacion de las entranas fuera del cuerpo.

Cuando extranas, me dijiste, habras dejado una parte de ti misma en el lugar que ya no tienes; el lugar que tal vez, por lo que sepas, ya no existe. Existiras endos pianos: enel cuerpo quete sigue, y en un pasado que asciende a una diapositiva de ti misma.

insectos, comoagua. Sigue hastala garganta, el estomago. Te encuentras a ti mismo en un lugar seco, esteril. Un hospital.

El proceso empieza antes de la ruptura. Los rasgos de la falta que viene se plantean en tus pasos por la vereda, en tus pensamientos sobre el grafiti en las paredes de los edificios, en las palabras de la ciudad y en tus mismas palabras. ^Cuanto tiempo falta para que me vaya? te preguntas. Cada dfa, escuchas que larespuesta disminuye. Un poco mas de dos meses. Dos meses. Un mes. Una semana. Tres dfas. Una hora. Treinta segundos. El tiempo que intentas sostener en la mano se convierte en corazones de manzanas tiradas.

Quizas entonces experimentes la sensacion del brote de la llanura dentro de tus miembros. La sensacion correpor tusmanos,como hilosvacfos que se escurren en la ruta de tus venas. Como

Contemplas esa frase que me escribiste alguna vez, la doble lejania. La lejania, el lugar que parece inalcanzable y tambien el espacio entre ese lugar y vos. El lugar que anoras, el lugar tan imposible quese separade tucuerpo. Y la doble lejania: algo infinitoaumentado. Como multiplicar cero por cero por cero, y en vez de terminar con el mismo cero, encontrar campos y desiertos de trigo secoyuna gargantacomocartonmagullado de los intentos de gritar cuando nadie te pudo escuchar.

Me dijiste una vez que tus sentimientos eran como el agua, que no los solias enmarcar. No entraban en vasos. Lo que tenias, me dijiste, era una pecera rota, el agua y los jirones de vidrio nadando por todos lados, inundandola casa.

Me parece que al final, esta todo ahf, frente a tus pies metidos en los centimetres de agua que cubre el suelo de tu casa. El agua te deja ver la ausencia como si fuera unapresencia. Y quieres sentir tus pies mojados, sin motivo sino para saber que estan ahf.

by Rocio Bravo

by Rocio Bravo

Veo tus manos morenas, quemadas por elsol, y me recuerdan quieneres tuy quien soy yo. Sontus manos,chapeadascon manchasobscuras lasquecuentan mihistoria, nuestrahistoria.

Siento tus manos y sientosu fortaleza, como las raices que sostienenla grandeza de unarbol. Sostengo tus manos ysiento su suavidad, como laarena caliente junto almar bajo el sol.

Son tus manoslas que mehan ayudado a seguir adelante, a nunca darme porvencida. Porque fueron tus manos las queme detuvieron cuandoempezaba a caminar. Fueron tus manoslas que medespidieron cuando medejaste en la universidad.

Tus manos, cansadas de trabajar, son simbolo delos obstaculos quehas tenido quepasar. Tus manos, cubiertas concicatrices, son muestra de tus luchasy de tiemposdificiles.

Porque han sido tus manos las que han piscado uva, fresa, mora y trabajado bajo el ardiente sol para darme ami lomejor.

Han sido tus manos las quehan injertado rosales para cambiarlosde color, w y a pesarde las espinasque te hanhecho sangrar, no cuentas de tudolor. O ^

Papa, veo tusmanos- quemadas, manchadas, cicatrizadas- y se quien soy.

Mama y su pajarillo | Andrea McWilliams | Digital Photography

Y tanto telo debo ati, Porque me hasensenado a luchar, a sonary a vivir. Porque han sido tusmanos las quenunca me han dejado sola Las que, cuando me gradue, merecen junto a mi recibir ese diploma.

Gracias papa, por loque me has dado,por las raices queme hasinculcado. Lo que tengo hoy es por ti, y espero que siemprerecuerdes que eres valorado.

Papa, no te preocupes,que ahila llevamos Y un dia,te comprare esa casagrande, y ya notendran que trabajar tus manos.

by Rocio Bravo

by Rocio Bravo

Que soledad que siento

Esta soledad que me no dejaser La que me acompana sin querer

Que soledad que no medeja ser feliz Porque miento al decirque estoy bien Y sonrio sin sentir

Que soledad la que empana mis suenos La queme quita mis ilusiones E invade mis deseos

Esta soledad me atormentaal dormir Cuando el silencio llena la noche Y la obscuridad me recuerda queno estas aquf

Que soledad la que llenami corazon Que se aduena de micuerpo A mi mente le quita la razon.

I heardthe ocean call myname.

With the excitement of childhood, My heart answered with a wild beat.

As fast as life would let me, I rushed toher side.

Leaving behind all that controlled whatI did,

I brought withme only what was me.

Bubbling with the joy of seeing an old friend,I reached totouch her hand. Reaching back for me with frothy fingers, she tickled my toes.

I danced back out of range just to tease.

Then—teaser that she is—she surged forward to tickle meonce more, up to m\

At her side I amas ageless as she is.

We are very young and very old, together at one time. She shares with me secrets of all time.

I share with her secrets of my life.

by Sara Mann

by Sara Mann

En esa epoca todos vivfamos a la deriva en paraguas sobre el mar. El agua estaba llena de paraguas y paraguas, todos blancos y puestos sobre la superficie boca abajo como tazas de te. Algunos viajeros boyaban dentro de sus paraguas en grupos de dos, o de tres o de cuatro. Algunos se movian empujados por la corriente. Yo flotaba solo. A veces la corriente me alejaba de las masas de paraguas y me dejaba girando en la bruma. Ninguno sabfa adonde nos dirigiamos. Hacfa un tiempo ya que yo giraba asf, solo, cuando te me acercaste. Una oleada habia w agarrado tu paraguas, y venias O con el pelo mojado y las manos ^ apretando el mango como para w salvarte la vida. Recuerdo tus 20 cejasTus meJillas coloradaspor

el vientosevero queperseguiatu paraguas. Tus jeans gastados, jaspeados conllovizna. Te ofreci el borde de mi paraguas para que te estabilizaras. "Gracias," me dijiste. Tu voz me parecia haber llegado de lejos.

La corriente dejo que flotaras cerca de mi en las estaciones que venfan. Como siempre en esa epoca de paraguas, ninguno de los dos sabfamos por donde ibamos, pero el agua debajo de tu paraguas por el momento estabatranquila. Nos vefamos de vez en cuando. Por las noches humedas, a veces nuestros rayos de metal se tropezaban, y por unos instantes mi paraguas enlazaba con el tuyo. Nos mirabamos a los ojos. Jugabamos cartas para ocuparnos. Tirabas reyes y ases desde tu paraguas al mio, las cartas cortando el aire

y salteando el agua y el alga marina entrenosotros. Siempre me ganabas. Un dfa te agarre la mano cuando estabas por coleccionar la baraja. Los dos paraguas quedaron quietos. "^Cuanto faltara para que te vayas?" Te pregunte. "^Como podrfamossaber?" Me habia acostumbradoa tuvoz de lejos.

Una madrugada sone con que habia una visitante en mi paraguas. Pense que sentia los puntos de sus dedos tocandome la espalda. Me desperte de repente. Caian sobre mi espalda unas gotas de agua tibia. Mi paraguas se habia inclinado un poco, como si estuviera preparandose para mecer. Por la tarde, los vientos aumentaron. Se movian paraguas y paraguas, miles de

paraguas en la lejania. Gritaste mi nombre. Tu paraguas tambien habia empezado a moverse. Nos despedimos con gestos. Despues de que te fuiste, los cuerpos dentro de los paraguas que me rodeaban empezaron a desaparecerse. Veia paraguas blancas flotando a mi lado y algunas veces escuche voces conversando, una risa, un llanto—pero cuerpos no habia. Te querfa encontrar, pero no sabia navegar. Ninguno de nosotros, de todos de nosotros en el mar, sabia navegar. Mi paraguas volvio a girar en las aguas profundas. Durante las tormentas del verano, a veces pensaba en encontrarte. Pensaba que quizas algun dia unmaremoto vendriay tetraeria

Kimberly Arredondo '11

Art/Photography Editor

AlexTudela '10

Layout Editor

Andrea McWilliams '12

Publicity Director David Hernandez '11

Established in the 1990s, SOMOS represents Latinos and Latino culture through prose, poetry, nonfiction, and visual art. For the spring 2010 issue, SOMOS is proud tobring an eclectic mix of voices and media.

Spanish Editor

Pablo Galindo-Payan '13

Portuguese Editor

Silvia Dos Santos-Pereira '12

Alejandra Ceja '12

Bianca Figueroa-Santana '10

Christian Martell '10

In Lily Meyer's short story "Most of the Way," Gonzalo, a commuter from Limache, Chile, contemplates the youth in Quillota and considers relations with Yesica, a prostitute,while he waitsfor the bus home. Alejandra Ceja writes about self-image and social stigma in a society that privileges a particular, put-together image. She examines "Social Capital" as she comparesherself to a girl whosehair is "light, soft, and TV-commercial shiny."

feeling by presenting the idea of "double lejanidad." Rocio Bravo, in "Soledad" and "Sin Ti," conveys the way solitude causes a physical and emotional numbness in one's being and strips the mind of reason. JuanRuiz's "Ya No QuedaNada," articulates loss, emptiness, and solitude and demonstrates how these feelings are intensified when contrasted with the beautiful memories of the past.

We see that in the this issue's art pieces spring has arrived. Students discover new, interesting perspectives on characteristically springthemes frombirds to trees, andcreated movement with their medium and technique.

Special thanks to:

Creative Arts Council, Third World Center, Undergraduate Finance Board, Salsa Ahmed, Mezcla, Student Activities Office

It is truly amazing to be able to read through the Spanish pieces and realize that this beautiful and dynamic language has a strong presence in the literature written by Brown. In "Las Horas del Agua," SaraMannconsiders themeaning of longing. She vividly depicts this

SOMOS has expanded this semester, with a growing editorial board and a greater number of copies to release. We are honored to present our Spring 2010 issue of SOMOS.

Sincerely, the SOMOSteam

The views expressed in this magazine represent those of the authors and artists, and not SOMOS or its staff.